Haunted Convent and Leper Hospital at Chacachacare Island

British West Indies

History

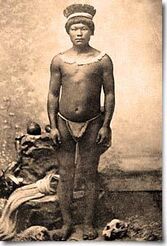

Amerindians original inhabitants of Chacachacare Island & surrounding area

Amerindians original inhabitants of Chacachacare Island & surrounding area

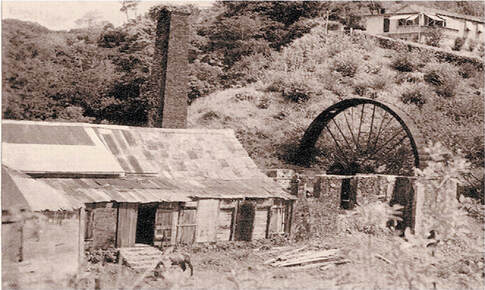

Chacachacare Island received its name by the Amerindians who populated the area. In 1498, Christopher Columbus named it El Caracol (the Snail). Presently it is part of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, and it lies in the Bocas del Dragon (Dragon’s Mouth), only seven miles from the coast of Venezuela. It encompasses approximately 900 acres. Between the period of 1777 and 1794, Spaniards established cotton plantations on the island, as well as whaling stations. By 1797, Chacachacare came under the control of the British. During the French revolution émigrés or Creoles from Santo Domingo and the surrounding islands settled here. Coconut, cocoa and sugar were also grown, with the biggest sugar mills in the British Empire being located on the island.

The Lepers

Example of watermills used on sugar plantation

Example of watermills used on sugar plantation

In 1814, there was a small population of lepers who resided in the Laventille hills to the east of the capital city of Port-of-Spain in Trinidad. They spent the day wandering the street and at this time there was talk by officials to establish a leper asylum on the Isla de Monos (Monkey Island), however there were too many residents living on the island, and recompensing them to leave their homes made the project too costly.

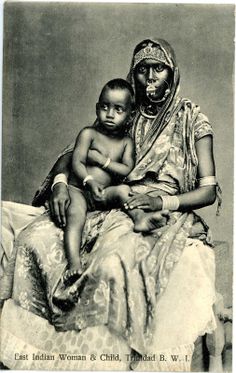

The situation was made more dire when in 1842, following the end of slavery, a tide of Indian immigrants who were promised five acres after five years were brought to Trinidad to satisfy the serious labor shortage. They brought a new influx of leprosy with them. Between 1842 and 1917, over 170,000 Asian Indians, Chinese and Portuguese (from Madeira) were enticed into working on the islands’ vast plantations. These indentured laborers from India were called “Bound Coolies”. The British colonizers on Trinidad became alarmed at the growing number of lepers who begged on the streets of the main city and in response the government bought an armory located at Cocorite, on the coast of Trinidad and established a leper colony at the site.

The disease became prevalent because unknown at the time it was spread by sneezing, and a person could be contagious for years without displaying any symptoms. If there was suspicion that a family member was infected with leprosy, the family kept quiet, as the stigma against this disease was so powerful, that just being a family member to a leper would alienate them as well.

The situation was made more dire when in 1842, following the end of slavery, a tide of Indian immigrants who were promised five acres after five years were brought to Trinidad to satisfy the serious labor shortage. They brought a new influx of leprosy with them. Between 1842 and 1917, over 170,000 Asian Indians, Chinese and Portuguese (from Madeira) were enticed into working on the islands’ vast plantations. These indentured laborers from India were called “Bound Coolies”. The British colonizers on Trinidad became alarmed at the growing number of lepers who begged on the streets of the main city and in response the government bought an armory located at Cocorite, on the coast of Trinidad and established a leper colony at the site.

The disease became prevalent because unknown at the time it was spread by sneezing, and a person could be contagious for years without displaying any symptoms. If there was suspicion that a family member was infected with leprosy, the family kept quiet, as the stigma against this disease was so powerful, that just being a family member to a leper would alienate them as well.

Dr. Louis de Verteuil the mayor of Port of Spain noted in 1857:

Leprosy is, unfortunately, very prevalent, and, of late years, appears to be even on the increase. It is much to be apprehended that the malady will continue to spread, and thereby entail an increasing amount of misery. An asylum was established under the government of Sir Henry G. McLeod, and is still maintained at the public expense, for the reception of lepers who are not in a position to support themselves. But as it is generally left to their option to enter the asylum or not, those only who make application are admitted, and, of course, lepers, who prefer a mendicant life, are seen going their rounds and begging, not only on the highways, but in the very streets of Port-of- Spain. Surely this ought not to be tolerated.

The Nuns

East Indian woman and child sent to BWI

East Indian woman and child sent to BWI

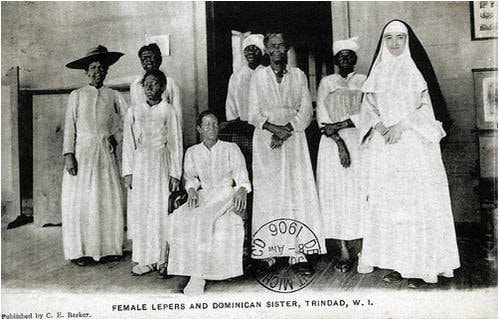

In 1868, the colonial government invited the Dominican sisters of St. Catherine of Siena to run the leprosarium. Fifteen Dominican Sisters of Etrépagny came to take over the care of the patients, however once there they fought a losing battle, as many of the infected patients which at one point numbered 300, would abscond to Port-of-Spain, spreading the disease in their wake.

The treatment for leprosy at this time was so painful, that many decided to live with the disease instead of enduring the efforts of the doctors to alleviate their symptoms.

A similar effort was made to isolate lepers in Hawaii when in January of 1866, the island of Molokai some fifty miles from Honolulu was made into a leprosarium.

In 1869, nine of the sisters died in a yellow fever epidemic and were interred at Lapeyrouse Cemetery. Sr. Marie Ceslaus Wingens, one of the original fifteen who contracted yellow fever survived, however she suffered from poor health until she died in 1897 in France. Sr. Marie Augustin Cartier also survived the yellow fever outbreak that took 15 of her sisters. For the next 28 years, she devoted herself body and soul to the care of the lepers in Cocorite, and died there in 1897.

The poor sisters were dogged by misfortune. In 1871, Sr. Marie Henri Reverdy arrived as a replacement, however her health was poor already, and the hardships of the place took their toll. She died in 1873, at the age of 30 only two years after serving in the Cocorite Leprosarium. By 1893, only one of the original sisters was alive, Sister Mary Augustine. During those 25 years since she arrived she had only spent 8 days outside the convent walls. Sr. Marie Ange arrived at the Cocorite Convent November 1897, and within 18 months in June 1899, she died. In 1910, Sr. Marie Eulalie Yvon who worked at the Cocorite Convent became ill, and died when she was only 45 years old.

The sisters were devoted, but infection from the lepers was only one of the risks; the backbreaking work, the heat, the insects and other illnesses prematurely claimed the lives of many of the nuns. Most of them never returned to France, or lived to an old age.

The treatment for leprosy at this time was so painful, that many decided to live with the disease instead of enduring the efforts of the doctors to alleviate their symptoms.

A similar effort was made to isolate lepers in Hawaii when in January of 1866, the island of Molokai some fifty miles from Honolulu was made into a leprosarium.

In 1869, nine of the sisters died in a yellow fever epidemic and were interred at Lapeyrouse Cemetery. Sr. Marie Ceslaus Wingens, one of the original fifteen who contracted yellow fever survived, however she suffered from poor health until she died in 1897 in France. Sr. Marie Augustin Cartier also survived the yellow fever outbreak that took 15 of her sisters. For the next 28 years, she devoted herself body and soul to the care of the lepers in Cocorite, and died there in 1897.

The poor sisters were dogged by misfortune. In 1871, Sr. Marie Henri Reverdy arrived as a replacement, however her health was poor already, and the hardships of the place took their toll. She died in 1873, at the age of 30 only two years after serving in the Cocorite Leprosarium. By 1893, only one of the original sisters was alive, Sister Mary Augustine. During those 25 years since she arrived she had only spent 8 days outside the convent walls. Sr. Marie Ange arrived at the Cocorite Convent November 1897, and within 18 months in June 1899, she died. In 1910, Sr. Marie Eulalie Yvon who worked at the Cocorite Convent became ill, and died when she was only 45 years old.

The sisters were devoted, but infection from the lepers was only one of the risks; the backbreaking work, the heat, the insects and other illnesses prematurely claimed the lives of many of the nuns. Most of them never returned to France, or lived to an old age.

CHACACHACARE ISLAND

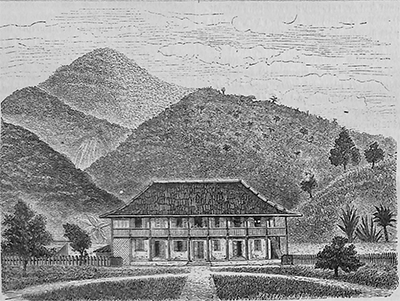

Convent at Chacachacare Island

Convent at Chacachacare Island

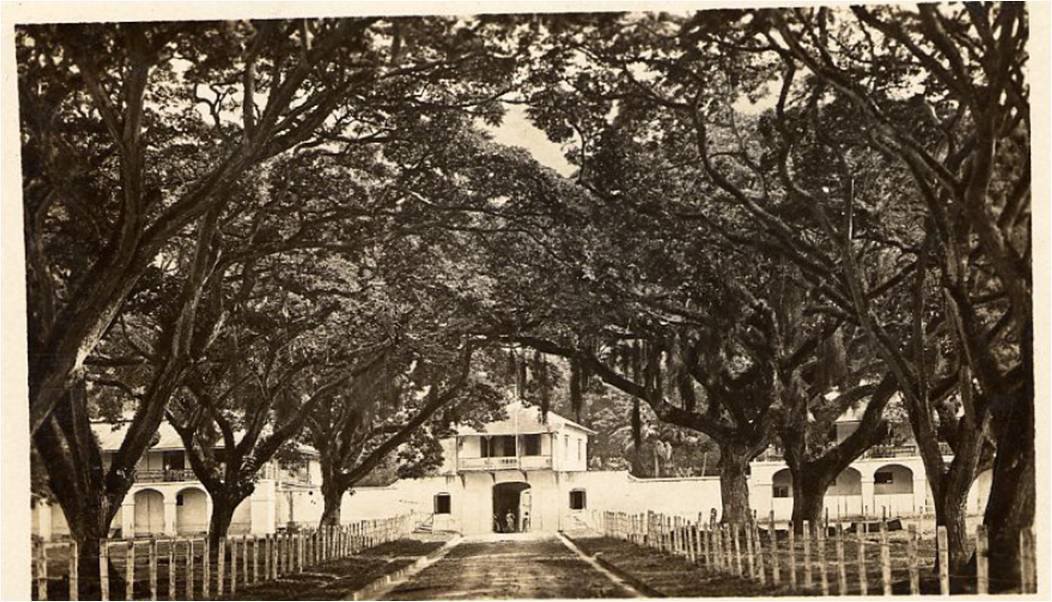

In 1915, an international conference determined that isolation of patients was the only way to stem the spread of leprosy. As a result, the colonial government in Trinidad made it mandatory that lepers should either be confined to their own homes, or else be taken to Cocorite by force. This proved to be only a temporary solution, and the government felt that only relocation off of Trinidad was a viable option.

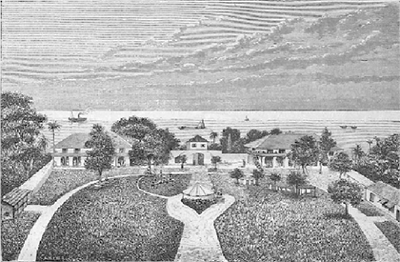

What came to mind was the island of Chacachacare. During the 1800s, Trinidadians had established a health spa and retreat there. In 1870, a lighthouse was built which was followed in 1887, by a stone pier and a large house to be used as a sanatorium. In 1880, the Dominican order had built St. Catherine’s Church, school and presbytery in a bay called La Chapelle; this was part of 80 acres donated to the Catholic church in 1842.

In 1920, using funds raised by an imposed tax on the citizenry, the government built a hospital, a common refectory, a bakery, kitchens, storerooms and patients’ cottages – on Coco Bay for men and Sanders Bay for women. This construction was done in secret and between 1922 to 1926, the patients were forcibly transferred there. Once the Cocorite buildings were empty, they were set on fire believing that they were contaminated.

What came to mind was the island of Chacachacare. During the 1800s, Trinidadians had established a health spa and retreat there. In 1870, a lighthouse was built which was followed in 1887, by a stone pier and a large house to be used as a sanatorium. In 1880, the Dominican order had built St. Catherine’s Church, school and presbytery in a bay called La Chapelle; this was part of 80 acres donated to the Catholic church in 1842.

In 1920, using funds raised by an imposed tax on the citizenry, the government built a hospital, a common refectory, a bakery, kitchens, storerooms and patients’ cottages – on Coco Bay for men and Sanders Bay for women. This construction was done in secret and between 1922 to 1926, the patients were forcibly transferred there. Once the Cocorite buildings were empty, they were set on fire believing that they were contaminated.

The Forgotten Diaries

Grave Sr. Mary Luigi, only nun from the Sisters of Mercy that died & was buried at Chacachacare

Grave Sr. Mary Luigi, only nun from the Sisters of Mercy that died & was buried at Chacachacare

The full story of the French Dominican nursing sisters who risked their lives looking after the lepers came to light only in 1993, when Marie Therese Retout, a member of the same Order, became the archivist at their Holy Name Convent in Port-of-Spain. She found, hidden away in an old storeroom, cobwebbed boxes riddled with termites. Inside were the diaries of the sisters who served on Chacachacare, all written in French. Sr Marie Therese made English translations of a heart-rending story of sheer determination to keep fighting a disease for which there was no cure until after the turn of the century”. (Above photos - Katherine Grillo)

THE HANSENIAN SETTLEMENT

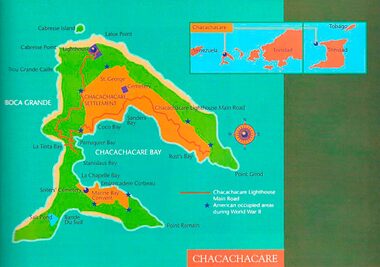

Map of Chacachacare Island

Map of Chacachacare Island

In 1922, plans were made to transfer the first wave of lepers to Chacachacare, however in order to avoid hysteria among the lepers and their families, the date of the first transfer to the island was kept secret. They chose the healthier ones to go first, as they could assist in completing the buildings on the island,

An entry from the nuns’ diary dated in 1922, recall the day the leper population at the Cocorite hospital were rounded up at 6AM, and escorted by policemen to the pier where they were taken to the island by a steamer.

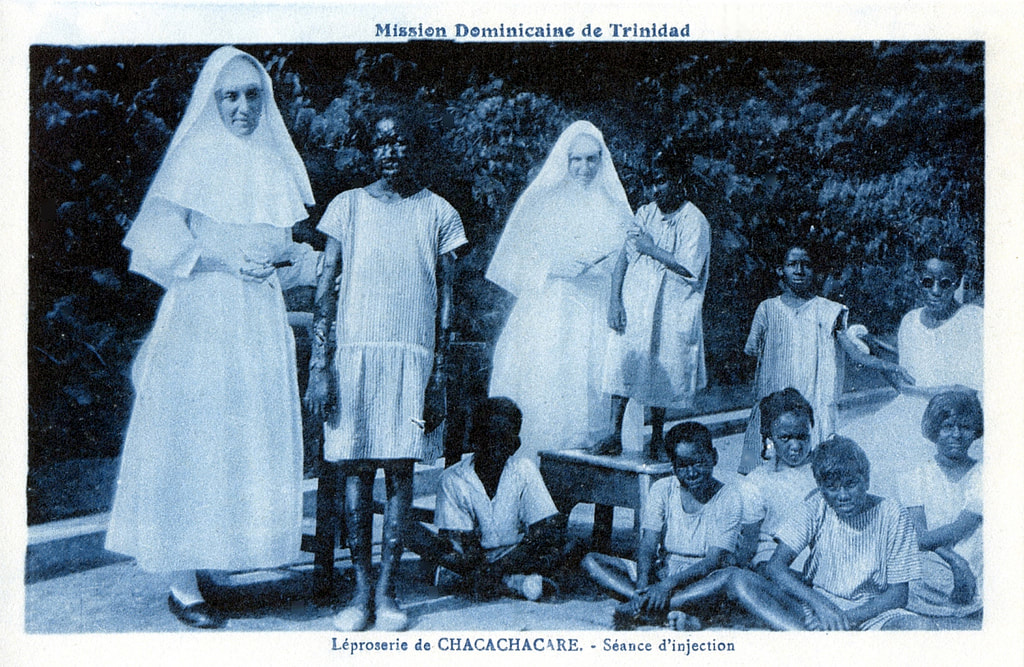

Food, water and medical supplies had to be brought in by boat, and the inhabitants of the island had to fight off mosquito-borne malaria as well as leprosy. There was no running water or electricity. The patients cared for themselves with the help of the sisters who helped to administer painful Intravenous injections. Once they could not care for themselves, they were taken to the hospital at Sunda Bay. This new leprosarium was known as the “Hansenian Settlement”.

An entry from the nuns’ diary dated in 1922, recall the day the leper population at the Cocorite hospital were rounded up at 6AM, and escorted by policemen to the pier where they were taken to the island by a steamer.

Food, water and medical supplies had to be brought in by boat, and the inhabitants of the island had to fight off mosquito-borne malaria as well as leprosy. There was no running water or electricity. The patients cared for themselves with the help of the sisters who helped to administer painful Intravenous injections. Once they could not care for themselves, they were taken to the hospital at Sunda Bay. This new leprosarium was known as the “Hansenian Settlement”.

Cursed

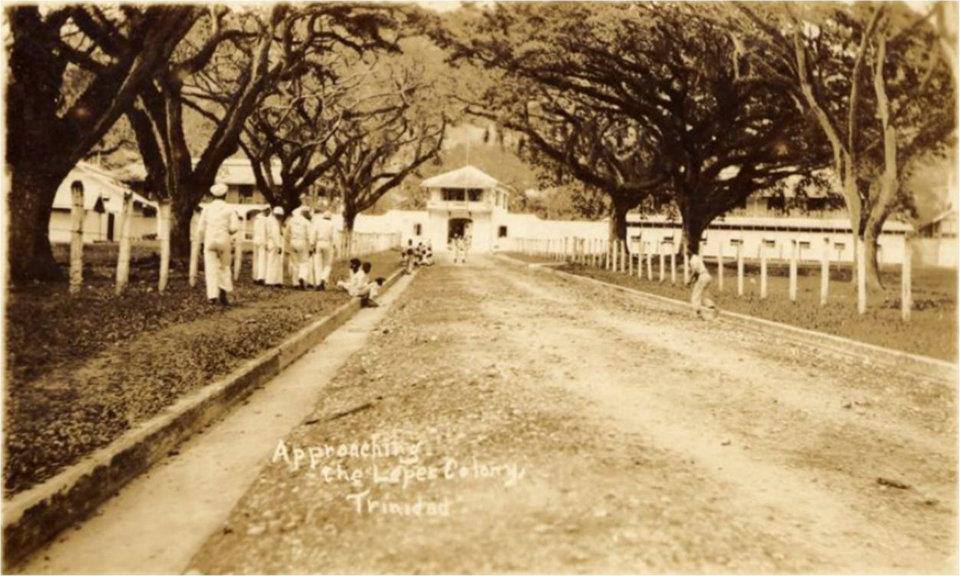

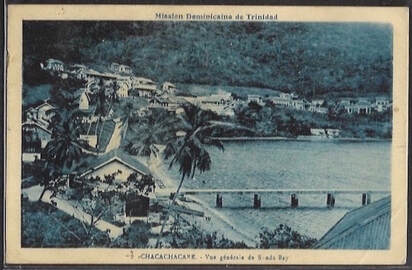

Chacachacare Island postcard

Chacachacare Island postcard

In 1926, on a hill overlooking Marine Bay, a new convent and chapel dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary was built for the sisters. In a small cemetery adjacent to the convent ten sisters were buried, many of them within a short time of arriving at Chacachacare. The first was Prioress Mother Marie who died only after 3 months on the island. Two years later in 1928, Sr. Joseph Agnés Ricaume died at Chacachacare after a short illness; she was 56 years old.

Another sister who came with the Lepers from Cocorite died at Chacachacare. Sr. Marie Elisabeth Hamard, fell ill shortly after arriving at the island, and lived in poor health until 1933, when she died at the age of 66.

A diagnosis of leprosy isolated not only the patients, but their caretakers as well. In 1927, Sr. Rose de Sainte Marie Vebert had already contracted leprosy. She suffered with the disease for 18 years, and lived in the women’s compound at Sanders Bay instead of the convent. The disease had taken away her sight, and had hideously distorted her once attractive face. Her tongue was so swollen she could barely speak.

Sr. Jeanne de St. Dominique Escoffier developed a skin infection which was wrongly diagnosed as Hansenian disease, and she was isolated from the other Sisters. For the next 13 years Sr. Jeanne was forced to live like a recluse. The medical doctor who had diagnosed her condition admitted years later, that he had made a mistake. The skin disease was not leprosy. By this time Sr. Jeanne had begun to suffer from paralysis. She died in 1931, at the age of 74 after serving the lepers at Cocorite and Chacachacare for 15 years.

In 1935, Sister Ena was also diagnosed with leprosy. She moved from the convent to Sander’s Bay where she lived in a cottage. Her remains were interred at the patients’ cemetery, and later a plaque was raised to her memory in the sisters’ cemetery. Another nun dropped dead from a heart attack after walking up the hill to the convent.

De Verteuil's Western Isles tells us that at the death of a sister, it was customary that a steamer went round the bay of Chacachacare with its flag flying at half-mast, and when passing in front of Marine Bay, blew its siren three times as a sign of sympathy with the sisters' bereavement.

On July 17, 1928, a storm struck the island and the roof of the convent was blown away, forcing the sisters to seek shelter among the patients. Instead of walking across the island, the sisters would take a launch from Marine Bay to the lepers’ village, and this was destroyed during this storm as well.

In 1934, Sr. Rosa Rawlins who was only 48 years old died. She had been working with the lepers since Cocorite, and had transferred to the island to continue to care for them; however she was often sick and died suddenly after being admitted to the emergency room at Port-of-Spain hospital.

Sr. Marie de St. Jacques Dressler arrived at Chacachacare in 1936. At this time no dentists were willing to come to the island to attend to the patients. The medical doctor asked that two Dominican Sisters be trained in dentistry. Sr. Marie de St. Jacques volunteered to be one of them. Both had to go to Port-of-Spain to receive an elementary formation from a dentist. They were taught how to extract teeth and to make dentures.

Sr. Marie Dominique Merle cared for the lepers for 25 years, and like Sr. St. Jacques Dressler left in 1950. They both went to La Desirade Island, close to Guadeloupe, to continue their work of mercy at this other leprosarium. She died in Guadeloupe in 1991. Sr. Dressler left La Desirade Island in 1970.

Sr. Christina Dillinger is one of the sisters that endured throughout the time the Dominican sisters worked with the leper colony. From Cocorite to Chacacharare she worked with the patients until 1950. She was then assigned to the Holy Name Convent in Port-of-Spain where she died in 1958.

Another sister who came with the Lepers from Cocorite died at Chacachacare. Sr. Marie Elisabeth Hamard, fell ill shortly after arriving at the island, and lived in poor health until 1933, when she died at the age of 66.

A diagnosis of leprosy isolated not only the patients, but their caretakers as well. In 1927, Sr. Rose de Sainte Marie Vebert had already contracted leprosy. She suffered with the disease for 18 years, and lived in the women’s compound at Sanders Bay instead of the convent. The disease had taken away her sight, and had hideously distorted her once attractive face. Her tongue was so swollen she could barely speak.

Sr. Jeanne de St. Dominique Escoffier developed a skin infection which was wrongly diagnosed as Hansenian disease, and she was isolated from the other Sisters. For the next 13 years Sr. Jeanne was forced to live like a recluse. The medical doctor who had diagnosed her condition admitted years later, that he had made a mistake. The skin disease was not leprosy. By this time Sr. Jeanne had begun to suffer from paralysis. She died in 1931, at the age of 74 after serving the lepers at Cocorite and Chacachacare for 15 years.

In 1935, Sister Ena was also diagnosed with leprosy. She moved from the convent to Sander’s Bay where she lived in a cottage. Her remains were interred at the patients’ cemetery, and later a plaque was raised to her memory in the sisters’ cemetery. Another nun dropped dead from a heart attack after walking up the hill to the convent.

De Verteuil's Western Isles tells us that at the death of a sister, it was customary that a steamer went round the bay of Chacachacare with its flag flying at half-mast, and when passing in front of Marine Bay, blew its siren three times as a sign of sympathy with the sisters' bereavement.

On July 17, 1928, a storm struck the island and the roof of the convent was blown away, forcing the sisters to seek shelter among the patients. Instead of walking across the island, the sisters would take a launch from Marine Bay to the lepers’ village, and this was destroyed during this storm as well.

In 1934, Sr. Rosa Rawlins who was only 48 years old died. She had been working with the lepers since Cocorite, and had transferred to the island to continue to care for them; however she was often sick and died suddenly after being admitted to the emergency room at Port-of-Spain hospital.

Sr. Marie de St. Jacques Dressler arrived at Chacachacare in 1936. At this time no dentists were willing to come to the island to attend to the patients. The medical doctor asked that two Dominican Sisters be trained in dentistry. Sr. Marie de St. Jacques volunteered to be one of them. Both had to go to Port-of-Spain to receive an elementary formation from a dentist. They were taught how to extract teeth and to make dentures.

Sr. Marie Dominique Merle cared for the lepers for 25 years, and like Sr. St. Jacques Dressler left in 1950. They both went to La Desirade Island, close to Guadeloupe, to continue their work of mercy at this other leprosarium. She died in Guadeloupe in 1991. Sr. Dressler left La Desirade Island in 1970.

Sr. Christina Dillinger is one of the sisters that endured throughout the time the Dominican sisters worked with the leper colony. From Cocorite to Chacacharare she worked with the patients until 1950. She was then assigned to the Holy Name Convent in Port-of-Spain where she died in 1958.

Winds of Change

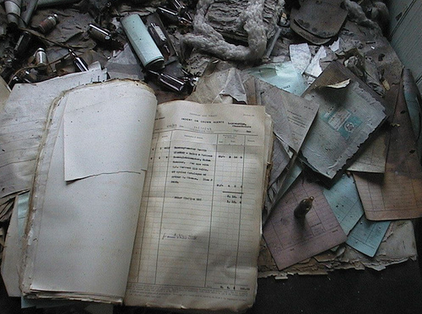

Files abandoned at Chacachacare

Files abandoned at Chacachacare

The morgue and cemetery for the patients was on the other side of the island by Sander’s Bay. At Rust's Bay, there was the Doctor’s House and at Blummer’s Bay the Nurse’s Quarters.

The lepers on Chacachacare had many rules they had to follow. There was no such thing as visitation rights since relatives were not allowed on the island, nor could the patients leave for extenuating circumstances such as bereavement. A strict watch was kept on the main jetty to ensure that no unauthorized contact from the mainland took place. Lepers were rationed to half a gallon (eight pints) a day for drinking only. All their clothes were washed in the settlement laundry. Patients were allowed to swim in the sea, but they could only bathe up to chest height. If caught in deeper water they served two days in the gaol on La Tinta Bay. The able bodied were compelled to work for the princely sum of 25 cents a day. In 1936, the doctor reduced this wage to 12 cents, and the lepers went on strike. In two months they got back their original wages. Some patients cultivated gardens in the wet season.

As war broke out in Europe a radio station was set up at Coco Bay, where the all inhabitants of the island could hear the events taking place around the world reducing some of their isolation.

In 1942, 1,000 U.S. and Puerto Rican Marines were stationed on Chacachacare and built barracks on the island, erecting a barbed wire fence to keep themselves separate from the leper colony. They helped the sisters by constructing a cable-tram from the jetty to the convent to enable the nuns to transport supplies more easily.

During the years of WWII it became more difficult to bring food to the island, and rigid rules preventing the lepers from fishing or growing their own food relaxed. Male and female patients who had lived in separate compounds on opposite ends of the island, took advantage of the lack of oversight from the government in Trinidad. Before long births increased, but babies were taken away from their mothers and sent to orphanages in Trinidad or placed with family members.

The sisters were assisted in their medical duties by paid government nurses who, for twice the normal salary, lived on the island in a “two weeks on-two weeks off” shift system. Understandably, the zeal of the paid nurses for the care of the lepers was not equal to that of the nuns.

By 1945, new drugs were introduced which allowed leprosy to be successfully treated, however the process was slow and painful and at the end of the year the nuns chronicled the population on the island, which was a total of 338 patients (237 males, 113 females and 38 children).

In 1946, electric generators were landed and installed with some difficulty, but they allowed patients a new form of recreation in the form of movies which were screened weekly.

Another change that occurred on the island was the establishment of a Hindu temple, or mandir which was opened in 1946 for the East Indian community.

The lepers on Chacachacare had many rules they had to follow. There was no such thing as visitation rights since relatives were not allowed on the island, nor could the patients leave for extenuating circumstances such as bereavement. A strict watch was kept on the main jetty to ensure that no unauthorized contact from the mainland took place. Lepers were rationed to half a gallon (eight pints) a day for drinking only. All their clothes were washed in the settlement laundry. Patients were allowed to swim in the sea, but they could only bathe up to chest height. If caught in deeper water they served two days in the gaol on La Tinta Bay. The able bodied were compelled to work for the princely sum of 25 cents a day. In 1936, the doctor reduced this wage to 12 cents, and the lepers went on strike. In two months they got back their original wages. Some patients cultivated gardens in the wet season.

As war broke out in Europe a radio station was set up at Coco Bay, where the all inhabitants of the island could hear the events taking place around the world reducing some of their isolation.

In 1942, 1,000 U.S. and Puerto Rican Marines were stationed on Chacachacare and built barracks on the island, erecting a barbed wire fence to keep themselves separate from the leper colony. They helped the sisters by constructing a cable-tram from the jetty to the convent to enable the nuns to transport supplies more easily.

During the years of WWII it became more difficult to bring food to the island, and rigid rules preventing the lepers from fishing or growing their own food relaxed. Male and female patients who had lived in separate compounds on opposite ends of the island, took advantage of the lack of oversight from the government in Trinidad. Before long births increased, but babies were taken away from their mothers and sent to orphanages in Trinidad or placed with family members.

The sisters were assisted in their medical duties by paid government nurses who, for twice the normal salary, lived on the island in a “two weeks on-two weeks off” shift system. Understandably, the zeal of the paid nurses for the care of the lepers was not equal to that of the nuns.

By 1945, new drugs were introduced which allowed leprosy to be successfully treated, however the process was slow and painful and at the end of the year the nuns chronicled the population on the island, which was a total of 338 patients (237 males, 113 females and 38 children).

In 1946, electric generators were landed and installed with some difficulty, but they allowed patients a new form of recreation in the form of movies which were screened weekly.

Another change that occurred on the island was the establishment of a Hindu temple, or mandir which was opened in 1946 for the East Indian community.

The Beginning of the End

Chacachacare Island electrical generating plant

Chacachacare Island electrical generating plant

By 1950, specialist surgeons were visiting the island to perform reconstructive surgery on the faces of inmates, whose features had been horribly disfigured by the disease, depriving them of noses, eyelids and lips.

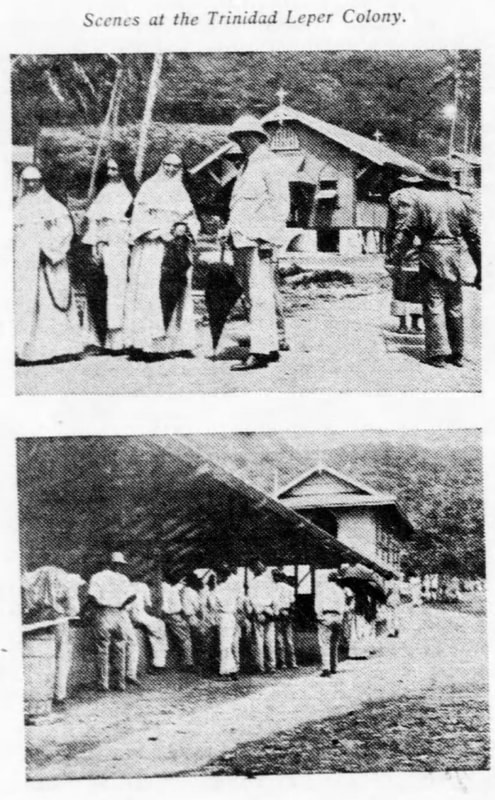

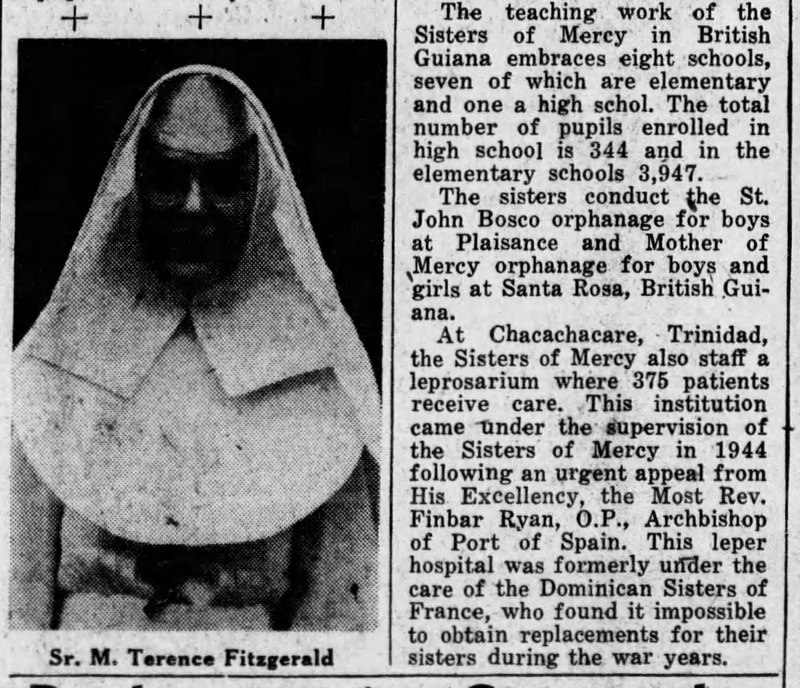

It was not only the dwindling number of Dominican nuns, but the government who in an effort to eradicate leprosy, insisted that the nuns who tended the leper settlement be nurses as well. To this end Archbishop Ryan persuaded the Mother Superior of the Sisters of Mercy in Baltimore, to send six nuns who were also registered nurses, to work alongside the Dominican Sisters. Between 1944 to 1950, the care of the leprosarium was transferred from the aging Dominican sisters who did not have enough replacements, to the Sisters of Mercy.

Initially four Sisters of Mercy from Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Savannah, began their mission as volunteers in the leper colony. In preparation for this assignment, they had each taken a 10 day course at the National Leprosarium at Carville, Louisiana. Awaiting the sisters’ arrival at Chacachacare were two other Sisters of Mercy already at the island.

By 1950, there were 500 patients, and four additional nuns came to help those already working there. During this time the Sisters of Mercy established a school for the children of the island.

In January 1955, 399 lepers staged a revolt and wrested authority from the island establishment, after a favored administrator Dr. Corros was dismissed. He had been allowing some of the patients to visit the mainland against the protests of the governor. The sisters had to call the police.

The reason why the Sisters of Mercy left is not clear. Maybe it was events like the leper revolt, the modernization of medical treatments or experiencing the vicissitudes which the Dominican sisters had endured for so many years. They left in 1955. Only one of their members, Sister Mary Luigi died and was buried at the nun’s cemetery in Chacachacare. The reason for her death was not listed, however stories are told of a fisherman who claimed to have found a white habit floating on the seas close to Chacachacare. It was attributed to a suicide by one of the nuns due to depression. Sister Mary Luigi is believed to be one of the ghosts that haunt the island.

There is not much information available as to who cared for the lepers after the Sisters of Mercy left, but it was most probably government nurses.

In 1970, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported on the leprosarium at Chacachacare which accommodated 248 patients. Many of the patients had come voluntarily from the surrounding islands, however most of the lepers stayed on the mainland and went to ambulatory clinics for treatment. The total number of patients at all the clinics was 1167, and it was roughly estimated that about 600 additional unknown cases existed. The lack of available resources was a considerable handicap in case-finding work, case follow-up and contact tracing.

The resources that were lacking were of course manpower. There was a dichotomy in the way the lepers were treated. There were many citizens who decried when the lepers were forcibly sent to Chacachacare Island, however there was still an overriding fear and stigma attached to working in any field coming in contact with one.

On July 24, 1984, the leper colony closed and the remaining patients, some of who had lived over 40 years on the island returned to Trinidad. During the time it had been opened over 2,000 patients had lived and died there.

It was not only the dwindling number of Dominican nuns, but the government who in an effort to eradicate leprosy, insisted that the nuns who tended the leper settlement be nurses as well. To this end Archbishop Ryan persuaded the Mother Superior of the Sisters of Mercy in Baltimore, to send six nuns who were also registered nurses, to work alongside the Dominican Sisters. Between 1944 to 1950, the care of the leprosarium was transferred from the aging Dominican sisters who did not have enough replacements, to the Sisters of Mercy.

Initially four Sisters of Mercy from Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Savannah, began their mission as volunteers in the leper colony. In preparation for this assignment, they had each taken a 10 day course at the National Leprosarium at Carville, Louisiana. Awaiting the sisters’ arrival at Chacachacare were two other Sisters of Mercy already at the island.

By 1950, there were 500 patients, and four additional nuns came to help those already working there. During this time the Sisters of Mercy established a school for the children of the island.

In January 1955, 399 lepers staged a revolt and wrested authority from the island establishment, after a favored administrator Dr. Corros was dismissed. He had been allowing some of the patients to visit the mainland against the protests of the governor. The sisters had to call the police.

The reason why the Sisters of Mercy left is not clear. Maybe it was events like the leper revolt, the modernization of medical treatments or experiencing the vicissitudes which the Dominican sisters had endured for so many years. They left in 1955. Only one of their members, Sister Mary Luigi died and was buried at the nun’s cemetery in Chacachacare. The reason for her death was not listed, however stories are told of a fisherman who claimed to have found a white habit floating on the seas close to Chacachacare. It was attributed to a suicide by one of the nuns due to depression. Sister Mary Luigi is believed to be one of the ghosts that haunt the island.

There is not much information available as to who cared for the lepers after the Sisters of Mercy left, but it was most probably government nurses.

In 1970, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported on the leprosarium at Chacachacare which accommodated 248 patients. Many of the patients had come voluntarily from the surrounding islands, however most of the lepers stayed on the mainland and went to ambulatory clinics for treatment. The total number of patients at all the clinics was 1167, and it was roughly estimated that about 600 additional unknown cases existed. The lack of available resources was a considerable handicap in case-finding work, case follow-up and contact tracing.

The resources that were lacking were of course manpower. There was a dichotomy in the way the lepers were treated. There were many citizens who decried when the lepers were forcibly sent to Chacachacare Island, however there was still an overriding fear and stigma attached to working in any field coming in contact with one.

On July 24, 1984, the leper colony closed and the remaining patients, some of who had lived over 40 years on the island returned to Trinidad. During the time it had been opened over 2,000 patients had lived and died there.

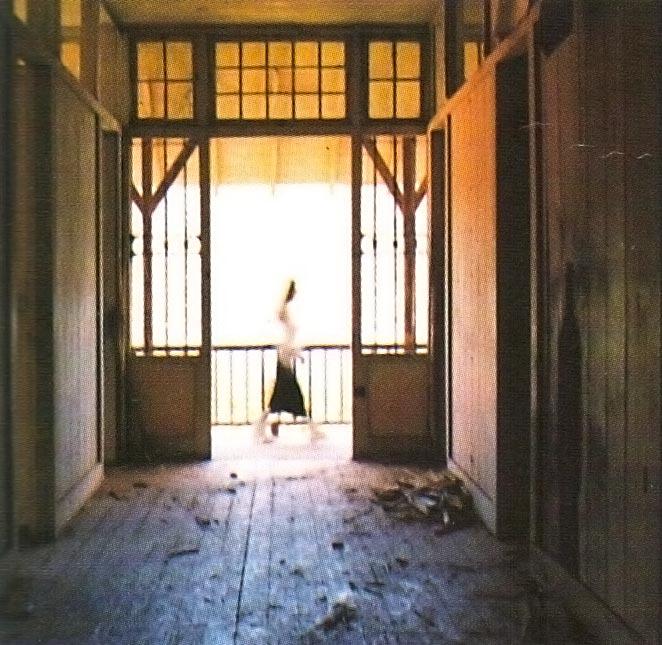

Ghost Reveal

Photo taken of apparition at Chacachacare Island

Photo taken of apparition at Chacachacare Island

Today, the Chacachacare Island Leprosarium is slowly but surely being reclaimed by the jungle. The buildings are empty and vandalized, empty holes where windows and doors once stood. Patient records and other medical equpment lay strewn around on the ground, left where they were last placed. The shell of the convent and chapel where the brave Dominican Sisters lived still stands, and the little graveyard containing the remains of nine of their order and one Sister of Mercy stand as a solemn reminder of the great price they paid for their unfailing devotion.

Frames of hospital beds and operating tables rust in the old hospital, and the ancient house where the medical superintendents once lived at Rust’s Bay is now a derelict ruin. The patients’ villages at Sander’s and Coco's Bay have vanished, succumbing to time and the weather. The St George Cemetery where patients were interred is now difficult to find, unmarked graves have been reclaimed by the land.

In the 1990s, the Trinidadian Coast Guard started using the old buildings as living quarters and established administrative offices and a security post. Within 6 months it was abandoned due to its reputation as being haunted. Today, Chacachacare remains uninhabited, except for staff maintaining a lighthouse on the island, and the Hindu Temple founded in 1945, continues to be functional with religious activities.

The locals stay away from Chacachacare Island for two reasons: fear of the supernatural, and fear that there is still some type of leprosy germs that can infect someone who stays there too long. This demonstrates the stigma that is attached to this still-feared biblical disease.

The best known ghost is that of a nun who was said to have committed suicide. There are different versions of her story. In one she falls in love with a Venezuelan sailor, and once their romance is exposed and she cannot continue to see him, she hangs herself over the chapel altar. In another version, her lover is a priest, and in a third her lover is a fisherman, and she kills herself after learning she is pregnant.

On Ghost Hunters International who filmed an episode there in 2011, they spoke to a priest who told them about an American nun named Sister Mary Luigi who was told to go to Guyana, and didn't want to. She was found dead in the water, and it was not verified if she had died by her own hand, or had fallen into the sea and drowned.

Whomever she may be, there are reports of a young nun haunting the convent, sometimes seen walking around with a lantern at night. Witnesses have also reported hearing voices, noises and footsteps, seeing apparitions, shadows, being pushed and feeling cold spots. Another ghost is that of a man who is seen at the jetty where boats dock on the island.

Boatmen talk of other “spirits” believed to roam the area around the patients’ cemetery. One fisherman is reported as refusing ever to set foot on the shoreline, even in daylight, in case he is “caught” by the spirits.

The Paranormal Investigators of Trinidad Tobago, tell about a group of coast guard soldiers that felt as though they were held down in their sleep, and being pushed up the stairs by an unseen hand.

There is a report of a woman in white wearing lipstick in the area of the nun’s cemetery. Another apparition is that of a man wearing a watch who has been seen in the doctor’s house.

Most people would probably think that any ghostly apparitions on the Chacachcare Island would be the nuns, however these ladies pretty much had their spiritual life in order. That one of them might have committed suicide and it was hushed up, or had some secret drama going on in her life that now holds her restless spirit trapped at the leprosarium is very possible.

Remember though, at least 2,000 persons suffering from leprosy came to live and die on this island during the 60 some years it served as a leper settlement. Many had to leave their families behind, others even had to give up their newborn children. There is little if any information given about those who received treatment on the island, much less about what when on among those that were trapped there.

There are probably many sounds and conversations that are caused by residual energy where so many lived, year after year, regulated by rules, obligations and vows they had taken.

Were there any murders, suicides, passionate liaisons and betrayals? Most probably there were, but living apart from the mainland these incidents were easily hidden, and even now there is no record of the personal lives of those people who had been exiled, and knew that a painful death sentence hung over their heads.

Research could not find any independent verification as to what happened to Sr. Mary Luigi however on her gravestone it shows she died January 1946. This date corresponds to the time when 29 Sisters of Mercy from the United States went to Guyana (then British Guiana) between 1935 and 1946 to minister.

Frames of hospital beds and operating tables rust in the old hospital, and the ancient house where the medical superintendents once lived at Rust’s Bay is now a derelict ruin. The patients’ villages at Sander’s and Coco's Bay have vanished, succumbing to time and the weather. The St George Cemetery where patients were interred is now difficult to find, unmarked graves have been reclaimed by the land.

In the 1990s, the Trinidadian Coast Guard started using the old buildings as living quarters and established administrative offices and a security post. Within 6 months it was abandoned due to its reputation as being haunted. Today, Chacachacare remains uninhabited, except for staff maintaining a lighthouse on the island, and the Hindu Temple founded in 1945, continues to be functional with religious activities.

The locals stay away from Chacachacare Island for two reasons: fear of the supernatural, and fear that there is still some type of leprosy germs that can infect someone who stays there too long. This demonstrates the stigma that is attached to this still-feared biblical disease.

The best known ghost is that of a nun who was said to have committed suicide. There are different versions of her story. In one she falls in love with a Venezuelan sailor, and once their romance is exposed and she cannot continue to see him, she hangs herself over the chapel altar. In another version, her lover is a priest, and in a third her lover is a fisherman, and she kills herself after learning she is pregnant.

On Ghost Hunters International who filmed an episode there in 2011, they spoke to a priest who told them about an American nun named Sister Mary Luigi who was told to go to Guyana, and didn't want to. She was found dead in the water, and it was not verified if she had died by her own hand, or had fallen into the sea and drowned.

Whomever she may be, there are reports of a young nun haunting the convent, sometimes seen walking around with a lantern at night. Witnesses have also reported hearing voices, noises and footsteps, seeing apparitions, shadows, being pushed and feeling cold spots. Another ghost is that of a man who is seen at the jetty where boats dock on the island.

Boatmen talk of other “spirits” believed to roam the area around the patients’ cemetery. One fisherman is reported as refusing ever to set foot on the shoreline, even in daylight, in case he is “caught” by the spirits.

The Paranormal Investigators of Trinidad Tobago, tell about a group of coast guard soldiers that felt as though they were held down in their sleep, and being pushed up the stairs by an unseen hand.

There is a report of a woman in white wearing lipstick in the area of the nun’s cemetery. Another apparition is that of a man wearing a watch who has been seen in the doctor’s house.

Most people would probably think that any ghostly apparitions on the Chacachcare Island would be the nuns, however these ladies pretty much had their spiritual life in order. That one of them might have committed suicide and it was hushed up, or had some secret drama going on in her life that now holds her restless spirit trapped at the leprosarium is very possible.

Remember though, at least 2,000 persons suffering from leprosy came to live and die on this island during the 60 some years it served as a leper settlement. Many had to leave their families behind, others even had to give up their newborn children. There is little if any information given about those who received treatment on the island, much less about what when on among those that were trapped there.

There are probably many sounds and conversations that are caused by residual energy where so many lived, year after year, regulated by rules, obligations and vows they had taken.

Were there any murders, suicides, passionate liaisons and betrayals? Most probably there were, but living apart from the mainland these incidents were easily hidden, and even now there is no record of the personal lives of those people who had been exiled, and knew that a painful death sentence hung over their heads.

Research could not find any independent verification as to what happened to Sr. Mary Luigi however on her gravestone it shows she died January 1946. This date corresponds to the time when 29 Sisters of Mercy from the United States went to Guyana (then British Guiana) between 1935 and 1946 to minister.