Drayton Hall Plantation

Charleston, SC Low Country

Marlene at Drayton Hall Plantation c.2006

Marlene at Drayton Hall Plantation c.2006

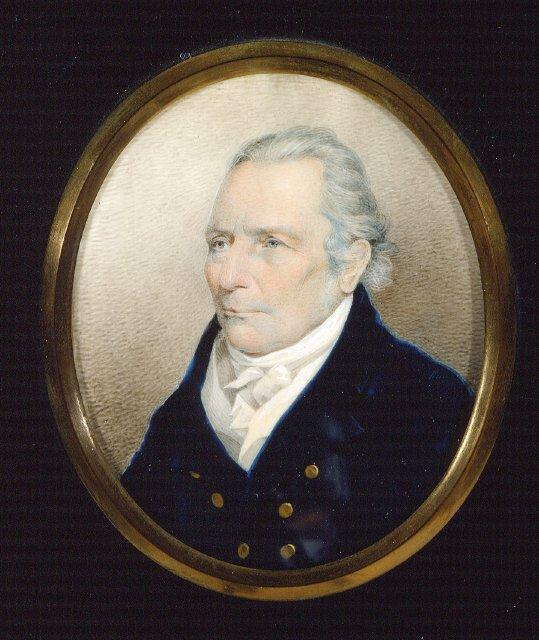

Edward Mayo was the first known owner of the piece of land where this plantation sits after he received a land grant for 750 acres in 1678. In 1681 he sold it to Joseph Harbin who built the first house on the property. In 2008 an archeological dig found evidence of an earlier structure hidden beneath the foundation of Drayton Hall. This early, unnamed plantation changed hands several times before 1738 when John Drayton (1715-1779), bought an 850 acre tract.

The Drayton family had arrived to South Carolina from Barbados aboard the ship Mary in 1679, bringing with them slaves and indentured servants. John’s father Thomas Drayton became a rancher who raised cattle on a 400 acre tract adjacent to the Ashley River and built his own home named Magnolia Plantation. He died in 1719, and his widow Ann (1680-1742) who never remarried became one the most successful female landholders of her time. It was her social status and financial holdings that allowed her children’s entry into the southern elite and ultimately set the foundation for her youngest son John to construct Drayton Hall. It was Ann who paid John’s outstanding property taxes, gave him twice the land his father bequeathed to him, and brokered his marriages into some of the most powerful families in the South.

The Drayton family had arrived to South Carolina from Barbados aboard the ship Mary in 1679, bringing with them slaves and indentured servants. John’s father Thomas Drayton became a rancher who raised cattle on a 400 acre tract adjacent to the Ashley River and built his own home named Magnolia Plantation. He died in 1719, and his widow Ann (1680-1742) who never remarried became one the most successful female landholders of her time. It was her social status and financial holdings that allowed her children’s entry into the southern elite and ultimately set the foundation for her youngest son John to construct Drayton Hall. It was Ann who paid John’s outstanding property taxes, gave him twice the land his father bequeathed to him, and brokered his marriages into some of the most powerful families in the South.

John Drayton Sr (1715-1779)

John Drayton Sr (1715-1779)

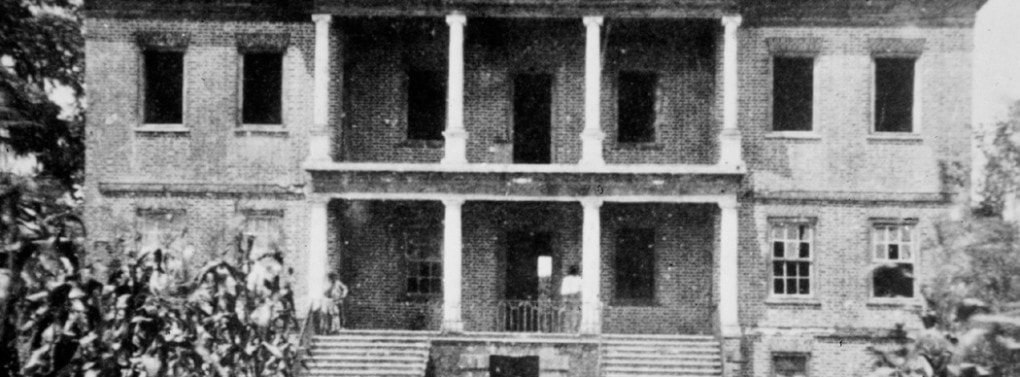

For many decades, the construction of the house was thought to have begun in 1738 and completed in 1742. In 2014, an examination of wood cores showed that the attic timbers were cut from trees felled in the winter of 1747–48 and the house is now thought to have been occupied starting only in the early 1750s. As the house was constructed, so were preparations made to grow rice, which required dirt walls called “banks” to be built, ditches and other forms of irrigation to keep salt water out and fresh water in. The rice grown in this area had its own particular name of Carolina Gold.

It took four years for Drayton Hall to be completed by European craftsmen. Richard Drayton grew rice and indigo, raised cattle and pigs, all tended by indentured servants, slaves and their freed descendants who were coopers, blacksmiths and carpenters. Their number varied throughout the years, but between 1790 to 1860 it averaged to about 45.

By 1740, Richard Drayton who was 25 years old had become a widower when his first wife Sarah Cattell and their two children had died. In 1741, he married Charlotta Bull who died in 1743 at the age of 23. She had already given Richard two children, and it’s possible her death was caused by complications in childbirth. In 1752, John married Margaret Glen who died in 1772. In 1775, when he was 60 years old he married Rebecca Perry, the 17-year old daughter of a neighboring plantation owner, the only wife to outlive him.

It took four years for Drayton Hall to be completed by European craftsmen. Richard Drayton grew rice and indigo, raised cattle and pigs, all tended by indentured servants, slaves and their freed descendants who were coopers, blacksmiths and carpenters. Their number varied throughout the years, but between 1790 to 1860 it averaged to about 45.

By 1740, Richard Drayton who was 25 years old had become a widower when his first wife Sarah Cattell and their two children had died. In 1741, he married Charlotta Bull who died in 1743 at the age of 23. She had already given Richard two children, and it’s possible her death was caused by complications in childbirth. In 1752, John married Margaret Glen who died in 1772. In 1775, when he was 60 years old he married Rebecca Perry, the 17-year old daughter of a neighboring plantation owner, the only wife to outlive him.

Rebecca Perry Drayton, (1758 - 1840) c.1809 (Source - National Portrait Gallery)

Rebecca Perry Drayton, (1758 - 1840) c.1809 (Source - National Portrait Gallery)

John Drayton as a wealthy farmer became a member of the Royal Governor’s Council, and his sons were educated as English gentlemen. He imported his furniture from England, and his gardens were designed in the English style, however their loyalties eventually lay with the colonies. One of the most fervent revolutionaries was his son William Henry (1742-1779) who was elected to Congress. He died unexpectedly the same year as his father while he was in Philadelphia attending Congress. He was only 37 years old, and no cause was given. He was buried in Philadelphia.

By the time the Revolutionary War broke out Drayton Hall had been standing for more than 20 years, and in 1779 the British army marched onto the extensive grounds. John Drayton fled with his family, however he died after suffering a seizure as he crossed the Cooper River. He was buried in an unmarked grave. He left behind four grown sons from his marriages to Charlotta Bull and Margaret Glen, along with his wife, Rebecca (1758-1840), and their three young children.

By the time the Revolutionary War broke out Drayton Hall had been standing for more than 20 years, and in 1779 the British army marched onto the extensive grounds. John Drayton fled with his family, however he died after suffering a seizure as he crossed the Cooper River. He was buried in an unmarked grave. He left behind four grown sons from his marriages to Charlotta Bull and Margaret Glen, along with his wife, Rebecca (1758-1840), and their three young children.

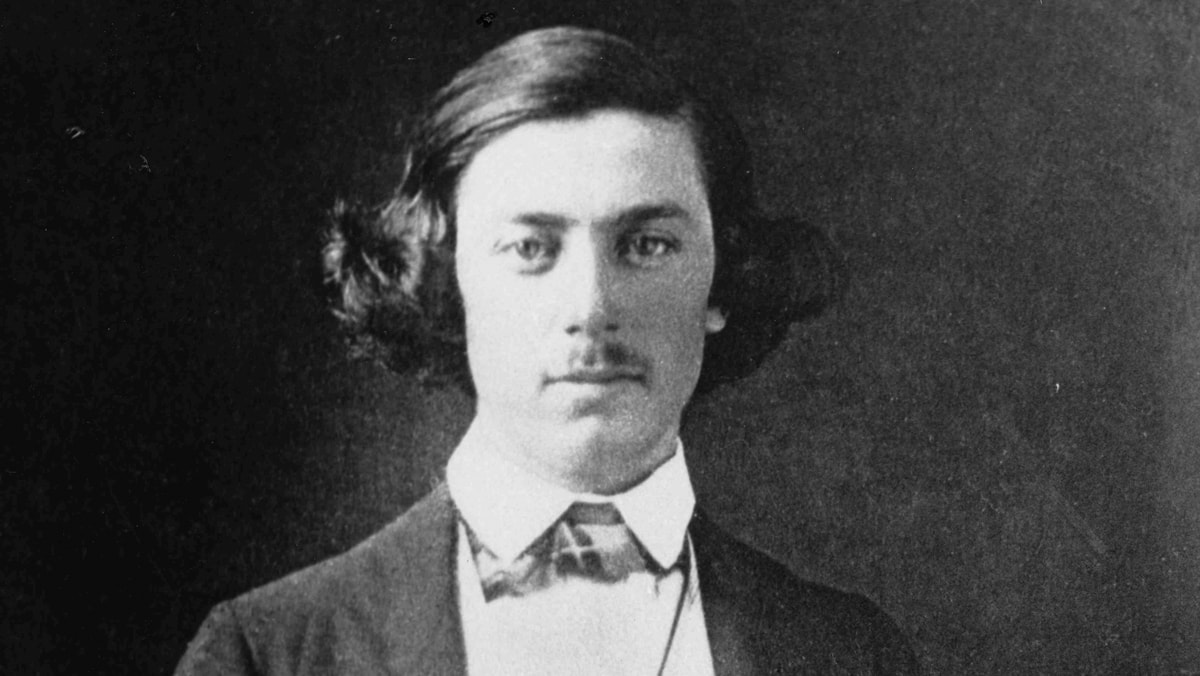

CHARLES H DRAYTON, I (1847-1915) He inherited Drayton Hall when he was 5 years old

CHARLES H DRAYTON, I (1847-1915) He inherited Drayton Hall when he was 5 years old

In 1780, the English returned and made Drayton Hall their field headquarters. At the age of 21, Rebecca Perry Drayton found herself a widowed mother. She managed Drayton Hall as the British army occupied its lands, and protected and ensured the survival of the estate her husband spent his lifetime creating. Both Sir Henry Clinton and General Charles Cornwallis stayed there along with 8000 soldiers, who encamped on the grounds around the plantation. By 1782, the British had been ousted and General “Mad” Anthony Wayne made this location his headquarters.

Rebecca’s stepson Charles Drayton (1743-1820) took ownership of Drayton Hall by the 1790s, after she sold it to him since she had inherited it.

Rebecca followed in her mother-in law’s footsteps and never remarried. By 1810, she had invested in over a dozen property holdings in Charleston. She was a renegade in a man’s world, claiming real estate in every corner of the city, and even secured properties for her daughters and her slaves. She transitioned from a teenage bride to a commanding entrepreneur. A widow for over 60 years, she used the law and her business acumen to expand the property holdings of her branch of the Drayton family tree.

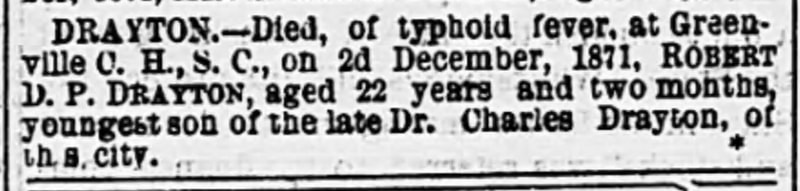

Charles died in 1820 and willed the home to his son Dr. Charles Drayton II (1785-1844) who in turned left it to his heir Charles III (1814-1852) who died at the age of 38 from pneumonia.

During the Antebellum period rice and cotton were cultivated and phosophate was mined. By the time the Civil War broke out, the plantation was no longer the family’s main residence, and when Charles III passed away his son was only five years old. At the beginning of the Civil War there were approximately 30 slaves, and by the end only a few remained. Northern troops came to Drayton Hall, and even now it is a mystery as to how it escaped destruction. An early story circulated of yellow flags posted at the entrance to signify it was a smallpox hospital by Dr. John Drayton. This gained credence in 2005 when unrelated letters were discovered describing Drayton Hall as a hospital, and it appears that it did serve in this capacity which is why it was spared.

Rebecca’s stepson Charles Drayton (1743-1820) took ownership of Drayton Hall by the 1790s, after she sold it to him since she had inherited it.

Rebecca followed in her mother-in law’s footsteps and never remarried. By 1810, she had invested in over a dozen property holdings in Charleston. She was a renegade in a man’s world, claiming real estate in every corner of the city, and even secured properties for her daughters and her slaves. She transitioned from a teenage bride to a commanding entrepreneur. A widow for over 60 years, she used the law and her business acumen to expand the property holdings of her branch of the Drayton family tree.

Charles died in 1820 and willed the home to his son Dr. Charles Drayton II (1785-1844) who in turned left it to his heir Charles III (1814-1852) who died at the age of 38 from pneumonia.

During the Antebellum period rice and cotton were cultivated and phosophate was mined. By the time the Civil War broke out, the plantation was no longer the family’s main residence, and when Charles III passed away his son was only five years old. At the beginning of the Civil War there were approximately 30 slaves, and by the end only a few remained. Northern troops came to Drayton Hall, and even now it is a mystery as to how it escaped destruction. An early story circulated of yellow flags posted at the entrance to signify it was a smallpox hospital by Dr. John Drayton. This gained credence in 2005 when unrelated letters were discovered describing Drayton Hall as a hospital, and it appears that it did serve in this capacity which is why it was spared.

Drayton Hall Plantation pond

Drayton Hall Plantation pond

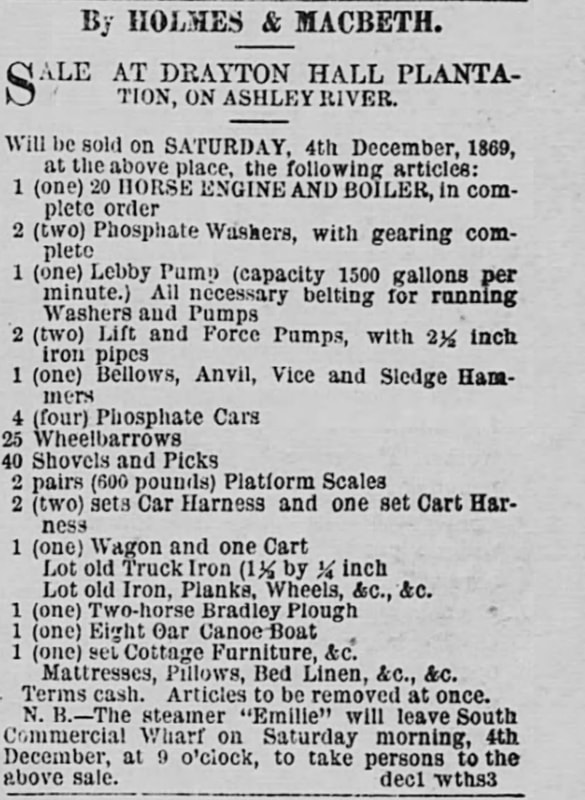

After the Civil War, Dr. John Drayton headed west to Texas where two of his brothers James and Thomas, who had joined the Texas Calvary now lived, but not before leaving several contracts in place to mine phosphate. His nephew Charles Drayton (1847-1915) went on to establish a mining company that operated from 1881 to the early 1900s. During that time, he built a narrow gauge railroad, fifteen houses, and two stores to support the mining operation.

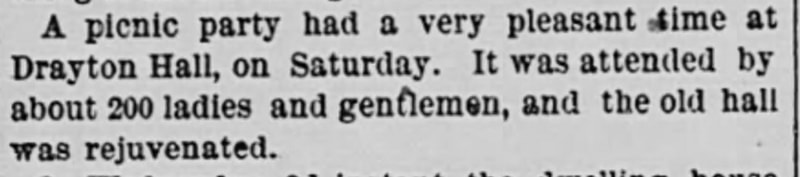

The mining operation allowed the Draytons to recover their wealth and by 1885 the house had been remodeled and a new roof added. The gardens were also renovated and a reflecting pool was constructed where a rice pond once stood.

In 1886 an earthquake destroyed the laundry, a flanker building next to the main home, and in 1893 the kitchen flanker was demolished by a hurricane.

The mining operation allowed the Draytons to recover their wealth and by 1885 the house had been remodeled and a new roof added. The gardens were also renovated and a reflecting pool was constructed where a rice pond once stood.

In 1886 an earthquake destroyed the laundry, a flanker building next to the main home, and in 1893 the kitchen flanker was demolished by a hurricane.

Capt Charles Henry Drayton, V (1887-1941) Fought in WWI

Capt Charles Henry Drayton, V (1887-1941) Fought in WWI

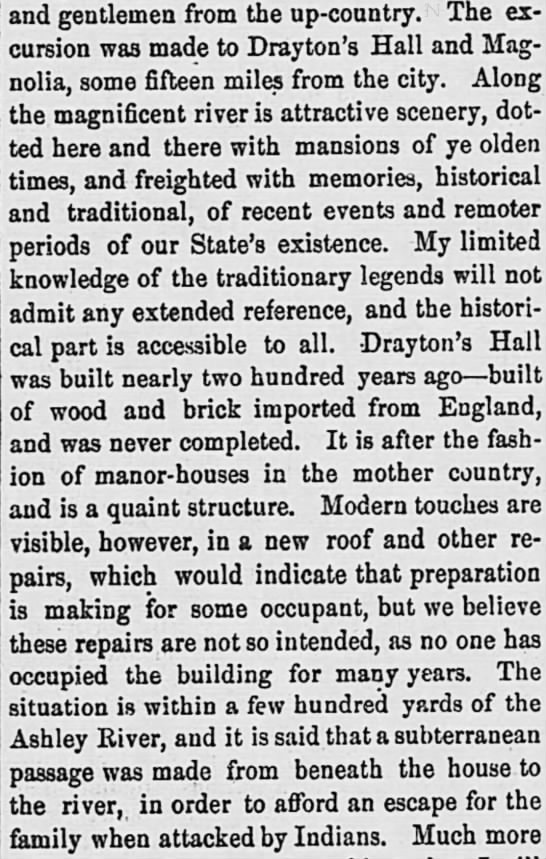

An 1875 newspaper article describes Drayton Hall as a charming home with beautiful gardens. A new roof had been installed, however it was described as being empty for several years. In the article it alludes to subterranean tunnels running between the house and the river, built by the original owners in order to escape an Indian attack.

During the last years that the Drayton family owned the property, they did not live there, and only went to spend an occasional weekend. Charles Drayton had 4 children, and it was his daughter Charlotta who spent the most time there, only using a wood burning stove and a refrigerator that received electricity from a caretaker’s cottage nearby. She last visited it in the 1960s and willed it to her nephews with a provision in her will asking not to modernize or make any major changes to the house.

Due to the costs of maintaining the home, her family sold it along with 125 acres to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The remaining acreage was sold to the State of South Carolina.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation acquired the home in 1974, and opened it to the public in 1977.

During the last years that the Drayton family owned the property, they did not live there, and only went to spend an occasional weekend. Charles Drayton had 4 children, and it was his daughter Charlotta who spent the most time there, only using a wood burning stove and a refrigerator that received electricity from a caretaker’s cottage nearby. She last visited it in the 1960s and willed it to her nephews with a provision in her will asking not to modernize or make any major changes to the house.

Due to the costs of maintaining the home, her family sold it along with 125 acres to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The remaining acreage was sold to the State of South Carolina.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation acquired the home in 1974, and opened it to the public in 1977.

The Ghost Reveal

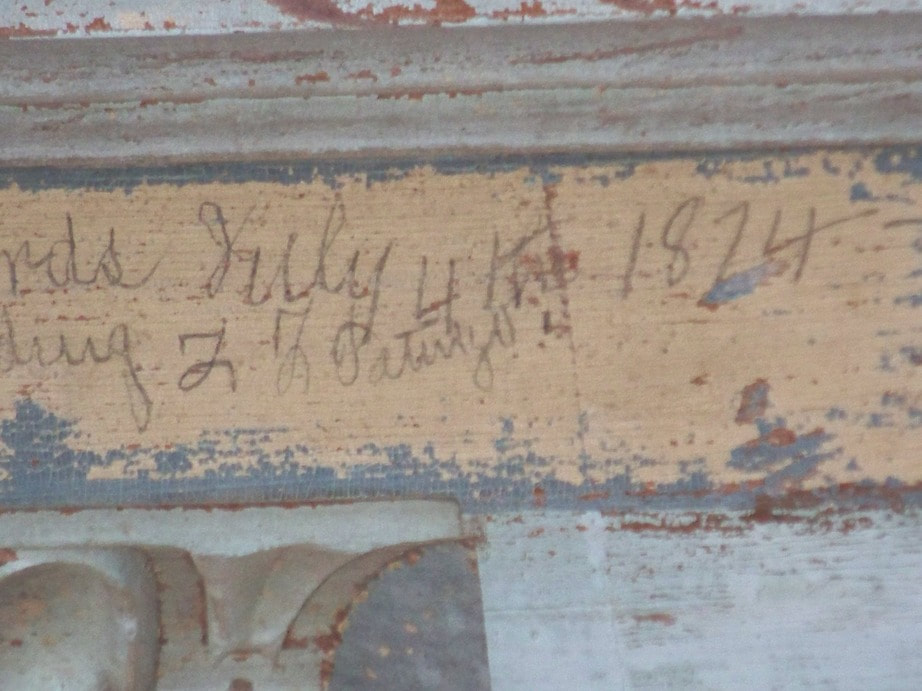

A narrow, hidden staircase used by servants and which led to a hidden room where Wm. Drayton was kept. c.2016

A narrow, hidden staircase used by servants and which led to a hidden room where Wm. Drayton was kept. c.2016

William Henry Drayton, the fiery revolutionary who died under mysterious circumstances in 1779, is believed to be one of the ghosts who haunts Drayton Plantation. In 2000, well-known medium, Elizabeth Baron who passed away in 2014, visited the home and described where she saw four men hanging from the trees, an execution which according to her was ordered by William Henry because they questioned his disloyalty to the crown. There is a narrow staircase at Drayton Hall that leads to a small, narrow room, where the family was reputed to lock up William Henry when he became belligerent after drinking too much, and fired up with patriotic fervor. His ghost is supposed to haunt this room, but especially the narrow staircase leading to it. This was also a staircase used by the slaves and servants of the home in order to pass unseen from one floor to the other. It is possible that it is their residual energy that is felt there.

In the 1980s, Pat Parker a docent at the Drayton Hall saw a man staring down from an upstairs window, and he was also seen walking down the oak-lined avenue. It is believed to be the ghost of William Henry Drayton.

In the 1980s, Pat Parker a docent at the Drayton Hall saw a man staring down from an upstairs window, and he was also seen walking down the oak-lined avenue. It is believed to be the ghost of William Henry Drayton.

African American cemetery at Drayton c.2006

African American cemetery at Drayton c.2006

The African-American Cemetery located on the grounds of the Drayton Hall Plantation is the resting place of at least 33 men and women. Richmond Bowens, a descendant of slaves owned by the Drayton family, was buried here along with his family members in 1998. In keeping with his wishes, the cemetery has been left natural, not restored or planted with grass or decorative shrubs. Most of the graves at Drayton belong to descendants of Bowens' great-grandfather, Caesar, who stayed on at the plantation after the end of the Civil War. The graves are aligned in an east-west direction, facing the rising sun, one of several African burial customs passed down to this day.

People with a Native American and African heritage known as "mustees" made up the Gullah culture found in the Low Country

The lives of the Drayton family and the servants that came with them from Barbados as well as their descendants were intertwined for many years. The Bowens family can trace back their lineage to one of the slaves that came on the ship with Richard Drayton in the late 17th century from Barbados.

An indirect connection is made with Tituba, a 17th-century West Indian slave who was the first to be accused of practicing witchcraft during the 1692 Salem witch trials. She said she knew about occult techniques from her mistress in Barbados, who taught her how to ward herself from evil powers and how to reveal the cause of witchcraft.

Even before the Civil War, the Revolutionary War provided an opportunity for the enslaved people on Drayton Hall to seek freedom.

People with a Native American and African heritage known as "mustees" made up the Gullah culture found in the Low Country

The lives of the Drayton family and the servants that came with them from Barbados as well as their descendants were intertwined for many years. The Bowens family can trace back their lineage to one of the slaves that came on the ship with Richard Drayton in the late 17th century from Barbados.

An indirect connection is made with Tituba, a 17th-century West Indian slave who was the first to be accused of practicing witchcraft during the 1692 Salem witch trials. She said she knew about occult techniques from her mistress in Barbados, who taught her how to ward herself from evil powers and how to reveal the cause of witchcraft.

Even before the Civil War, the Revolutionary War provided an opportunity for the enslaved people on Drayton Hall to seek freedom.