By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories

On a frigid day in January, 1910, the Chicago headlines trumpeted, "Chicago Fiend Second White Chapel Ripper".  Brothel at 310 North Peoria Street in Chicago c.early 1900s Brothel at 310 North Peoria Street in Chicago c.early 1900s

The reason for the sensational story was based on the opinion of Assistant Police Chief Schuettler, following the coroner's report for a post-mortem completed on the body of Mrs. Jennie Cleghorn (AKA Anna Furlong). She had been found mutilated and decapitated in a South Side rooming house, which doubled as a brothel situated over a saloon owned by James Seeley at 1702 Armour Avenue (also given as 51 West 17th Street). Little did the police or the public know that this grisly crime was only the beginning.

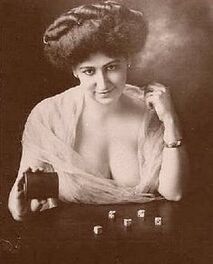

. A few years before, Lizzie Borden was acquitted of killing her parents, and Jack the Ripper had stalked the streets of London. Closer to home H. H. Holmes had lured his victims who were visiting Chicago to his notorious Murder Castle, and swung from the gallows in 1896. The police believed the murderer had crept into the woman's flat while she slept, but it was a mystery as to how he had gained entry. He strangled her since her trachea had been crushed, and then with a dull knife he went on to chop, hack and slash the woman's body. Other stories described the murder weapon as an ax. The police found her body clad only in a nightgown. The room reflected that the woman had fought terribly for her life. The furniture and walls of the room were splattered with blood. The killer cut out her heart and other organs. and then replaced them inside the body cavity. In an effort to hide her identity, he took the head. Her scalp had been torn from her skull and was found with an ear attached, under the bed wrapped in bed clothing. The police also found that the incisions made on the body were done with surgical skill. The following is one of the stories that details the story (The Dayton Herald, Jan 20, 1910), of this horrid discovery on a very cold winter day in the Windy City’s South Side: The head could not be found but part of the right ear and the scalp above it remained on the bed. The dull knife which was used to sever the head had also been used freely on the trunk. Across the abdomen were half a dozen long slashes and the knife had evidently been plunged several times into the vitals.  Pearl Dorset, levee character, associated with the Nat Moore case, sitting in a room in Chicago. She was probably associated with prostitution or other vice. Pearl Dorset, levee character, associated with the Nat Moore case, sitting in a room in Chicago. She was probably associated with prostitution or other vice.

The Paris was a saloon and brothel in Chicago's Levee district, located at 2101 Armour Street. It was only a few blocks from the scene of the crime in a similar establishment. The owner of this one was convicted of running a white slavery ring.

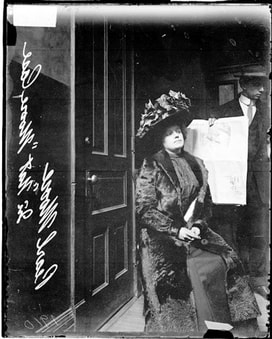

A few days before the discovery of Jenny Cleghorn's body, the already notorious tenderloin area of Chicago made the newspapers with the death of Nathaniel "Nat" F. Moore. He was the son of James Hobart Moore, one of the brothers who controlled the Rock Island Railroad system. He died after 54 hours of debauchery while in the brothel belonging to Veronica "Vic" Shaw, located at 2014 Dearborn Street. The coroner said his heart had given out. Moore would leave his young wife alone at their apartment at 1100 Lake Shore Drive. She was formerly Miss Helen Fargo, a New York society girl. It seemed that Nat was attracted to the "bad girls". "Big" Fitzgerald, saloon-keeper at 12th Street and Wabash Avenue, formerly Nat Moore's chauffeur, had gone to a levee saloon with him where they drank wine, and then after closing hour they went to the Shaw resort. The week before Moore had written out a check for $1,500 in payment of his last "carousal bill" at the brothel. In those years that was a small fortune.  South Dearborn Street, Chicago, c.1911 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, c.1911

Madame Vic Shaw was married to Roy Jones who was a red light saloon keeper. He and Pearl Dorset an inmate at the Shaw whorehouse, were the ones who told the police of the hours preceding Moore's death. They had called Dr. M.F. Murray when Moore complained that he couldn't sleep. Moore asked him for unadulterated morphine, but the doctor refused. Instead the doctor gave him injections of morphine, adulterated with sulfate of atropin. Later, the cause of death was given as heart failure.

Moore had an income of $50,000 per year which he had spent in "wild and riotous living." His escapades had made him a national character. He had received $750,000 on his 21st birthday. He was 25 years old when he died.  Helen Fargo Moore Arnold c.1912 Helen Fargo Moore Arnold c.1912

Nat Moore's young widow was described as prostrate with grief, and after the burial she left to New York, however by October she had returned to Chicago.

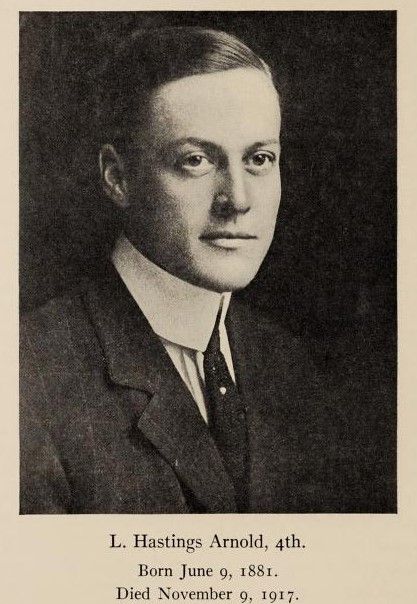

Heartbroken or not by October, 1911, she married Lemuel Hastings Arnold IV. Like her first husband, Lemuel was wealthy. He came from a prominent New England family that dated back to the Revolutionary War. One of his ancestors was a member of the Continental Congress, and his great- grandfather was governor of Rhode Island. An uncle had been a general in the Civil War. Lemuel Hastings Arnold might have come from a prestigious family, but he was not immune to bad luck in his personal life. In 1905, he married Marie Hoisington Woodbury Holmes a divorcee and widow with a mysterious past. One of her prior engagements was broken after it was exposed she was an "adventuress". Four years after the marriage she went to Reno and asked for a divorce from Lemuel. Within months of securing her divorce she married Samuel Willetts.  Young Chicago prostitute c.early 1900s Young Chicago prostitute c.early 1900s

It seemed Lemuel Arnold's luck turned when he married Helen Moore in 1911, but within six years he was dead at the age of 35. There was no mention of his death in the newspapers, and considering the prominence of the family, this seems strange, unless the circumstances of death could be embarrassing like a suicide.

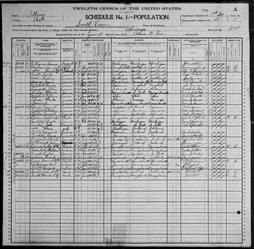

Perhaps it was the notoriety of Nat Moore's death in a South Side brothel, which gave more than normal attention to Annie Furlong's savage murder. It was during the police investigation that her true identity became known as Jennie Cleghorn. Police were mystified how a 51 year old woman came to live upstairs from a mixed race saloon, which were known to be brothels. She appeared to come from a genteel background, and witnesses who knew her, said she once owned considerable property in Englewood. Her nails were carefully manicured, and fashionable clothing was found in the closets of her room. She said her husband, Hugh Cleghorn made her convert her property into cash, after which he abandoned her for another woman.  Census for Jennie Cleghorn and her husband Hugh c.1900 Census for Jennie Cleghorn and her husband Hugh c.1900

Review of the 1900 census confirms her claim. She lived in Chicago and ran a rooming house along with her husband with several male boarders.

Without a husband or property, friends deserted her, and she drifted to the underworld of St. Louis. There she remained until five or six months before her murder when she moved back to Chicago. On January 24, Jennie’s head was found in a vacant lot at 251 Armour Ave which was six blocks away. Two small boys came across something wrapped and frozen inside four towels. It was the victim's head with her mouth cut from ear to ear. The skull was crushed. The police believed it had been thrown there since the day of the murder. During those days after Jennie's murder, Hugh Cleghorn of Geneva, Wisconsin came forward to identify himself as the victim's husband, but stated that he would have nothing further to do with the case. More than likely he was trying to verify if she had any money or jewelry he could claim. In essence he left her to be interred in a potters grave at the Cook County cemetery, where indigents ended up. Strangely in April, 1910, four months after Jennie's killing, Hugh Cleghorn was listed as living with his wife Blanche and their 17-year-old son Walter on the census. Had he married after Jennie's death, and Walter was a son from a previous marriage, or was he a bigamist? There is proof that Jennie Clark married Hugh Cleghorn on March 11, 1894 in Chicago, but he would not be the first person to be leading a double life especially if his spouse lived in another state.  A member of the anti-vice Midnight Mission (left), and Levee district prostitutes walking the street (c.1911) A member of the anti-vice Midnight Mission (left), and Levee district prostitutes walking the street (c.1911)

During this investigation, Coroner Hoffman noted the coincidence that on the same date of January 20, two years before, almost to the hour, another woman was murdered.

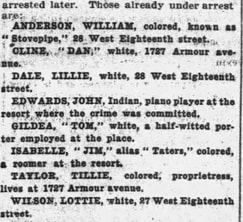

She was found in Lake Michigan off Jackson Park. She was nude and the corpse was headless. A portion of the lower jaw clung to the torso. The top of the head was completely missing. Most of the bones in the body were broken and the police wondered if the body had also been caught in a steamer's propellers. They woman was estimated to about 25 years old, stood 5'5" and was blonde. She had been nude when she went into the water, 1 month to 2 weeks before the discovery of the body. The theory was entertained if the women had been victims of some secret cult or organization that used this date as a special anniversary. The victim was never identified.  Arrestees in the Jennie Cleghorn murder which were all eventually released c.1910 Arrestees in the Jennie Cleghorn murder which were all eventually released c.1910

Shortly after the Jennie Cleghorn's murder, the police were considering several of the visitor or roomers as suspects and detained them, even going to Louisville to bring one of them back to Chicago. They even considered the idea the murderer was female.

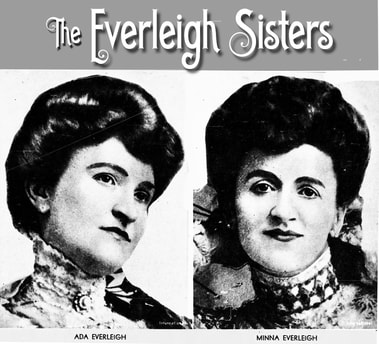

The police described the "woman's murder as one of the worst crime in the history of Chicago's underworld." A clue found in the room was a man's celluloid collar, size 17, with a black bow tie. A butcher's knife with a dull blade, which showed evidence of having been wiped on a piece of newspaper, was found to be the murder weapon. Like the Ripper murders the coroner believed the killer had some knowledge of anatomy. Those detained were all released, and by the end of 1910 the police had no leads, but that changed a few months later, when another murder was committed.  Ada and Minna Everleigh were madams of an upscale Chicago brothel Ada and Minna Everleigh were madams of an upscale Chicago brothel

However, not all Chicago brothels were dark and dangerous places. Aida (Ada) and Minna Everleigh, born Ada and Minna Simms, were two sisters who operated the Everleigh Club, a high-priced brothel in the Levee District of Chicago during the first decade of the twentieth century. They catered to men with deep pockets.

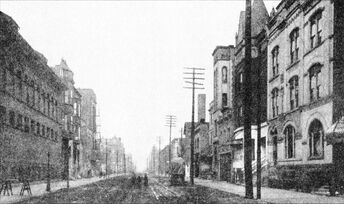

Neither married, and technically died spinsters. Minna passed away in 1948, age 82, and Ada in 1960, age 95. They are both interred in the family's plot in St. Paul's Cemetery in Alexandria City, Virginia. But for other women, working in a Chicago whorehouse could prove to be quite deadly. In May 1910, four months after Jennie Cleghorn's death another victim was found murdered. She was killed in a West Side rooming house located at 133 South Morgan Street, with her head nearly severed and the body terribly slashed. The young woman's body was found fully clothed within ten hours of her death. The room exhibited evidence of a terrific struggle. The golden-haired girl remained unidentified, and her murder unsolved.  South Dearborn Street in the Levee, c. 1911. The Everleigh Club, a notorious high-priced brothel, is on the far right. These murders took place in this Chicago tenderloin area infamous as a red-light district from the 1880s until 1912 South Dearborn Street in the Levee, c. 1911. The Everleigh Club, a notorious high-priced brothel, is on the far right. These murders took place in this Chicago tenderloin area infamous as a red-light district from the 1880s until 1912

In June 1910, Galesko Enchevy (also spelled Alseco Inchevy, Galesko Enchev, Galenco Enchiff) was arrested for the murder of Jennie Cleghorn. It appeared he had told several persons that he had committed the murder. When police searched his room they found a book on surgery, a pair of surgeon's shears and a dirk knife that appeared stained with blood.

After his arrest, he was sent to Cook County Insane Asylum at Dunning. Then he was deported to his native Bulgaria where he escaped from an insane asylum, then smuggled himself back into the United States. Two years passed, and the newspapers reported on the death of the Pfanschmdit family. They claimed it was the work of the axman who had killed several families in the Midwest, and he had returned to Illinois. The family consisted of the parents, their daughter Blanche, and a fourth person Emma Maempen. They were killed in the house, and then it was burned down. The newspapers said the number of the axman's victims totaled 26.  Galesko Enchevy a Bulgarian national confessed to the murder. He would return to the US after being deported, and there is suspicion he was tied to other murders in the Midwest (Source - Chicago Tribune c.1910) Galesko Enchevy a Bulgarian national confessed to the murder. He would return to the US after being deported, and there is suspicion he was tied to other murders in the Midwest (Source - Chicago Tribune c.1910)

By 1914, Assistant Chief Schuettler suspected that Galesko Enchevy the confessed slayer of Jennie Cleghorn was the axman. He wrote incoherent, taunting letters to Schuettler. It was during these years that the various killings of families throughout the Midwest were reported.

Schuettler described where each murder occurred just after the change of the moon from the last dark quarter, and always on Sunday nights, which alienists reported as when most lunatics were active. The crimes were committed as the killer moved eastward along railroad lines. In 1914, another family had been slain on Blue Island, again with the use of an axe. What became of the man responsible for what became known as the Midwest Ax-Man Murders were never solved, as were the killings of the three women in Chicago between 1910 to 1912. Was it the work of the same person? This question also remains unanswered. Source - Chicago Tribune

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed