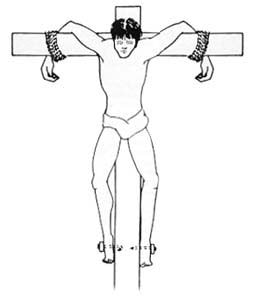

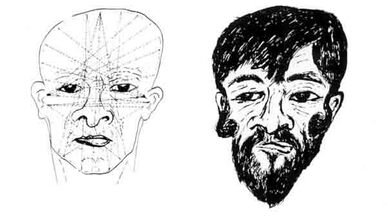

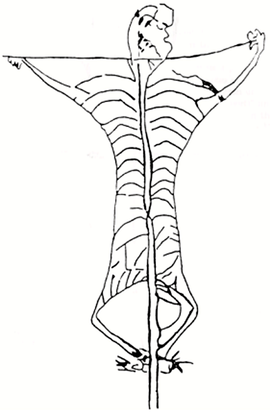

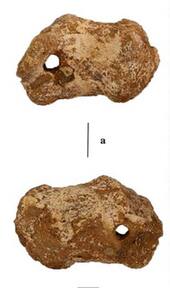

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories In ancient Rome, crucifixion was a painful way to execute criminals and slaves, and to remind the populace the consequences of breaking Roman laws. Rare archaeological evidence has been found through skeletal remains that confirm this type of execution.  Crucifixion in antiquity was a gruesome execution. (Source - Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1985) Crucifixion in antiquity was a gruesome execution. (Source - Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1985) Crucifixion did not originate with the Romans. The Assyrians, Phoenicians and Persians practiced this form of execution 1,000 yeas before the birth of Christ. It was introduced into western cultures from the east. Some Greeks used it, mostly the ones who had contact with Phoenicians and Carthaginians. After Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., crucifixion was used by the Syrians and the Ptolemies who ruled Egypt. The traditional method of execution among Jews was stoning, even though some Jewish rulers did crucify their own people. The Romans employed it in the first century B.C. mostly as punishment, not executions for non-Romans, most of them slaves. The slave would march through the streets declaring their offense with a wooden beam placed on his neck, and bound to his arms. The humiliation acted as a way for the person to expiate their crime. Eventually the process increased to include being stripped and scourged. The purposed was to frighten disobedient slaves, not to kill them. Eventually it evolved into a form of execution for certain crimes. Then it wasn't only slaves who endured this, but foreign captives, rebels and fugitives to quash a rebellion or during wartime. Captured enemies were executed in masses. In 71 B.C. when Spartacus led the slave revolt, the Romans lined the road from Capua to Rome with 6,00o crucified rebels. When thousands were being executed due to war, the crucifixion was carried out mostly by a soldier from the ranks of Roman legionaries, and the process was haphazard. In peace time, it would take place at a certain time and place, and could only be authorized by special persons in the Roman court. Emperor Constantine banned crucifixion in the fourth century A.D. Golgotha in Jerusalem was a particular site where crucifixions would take place. Outside of Rome, only a Roman procurator had the authority to sentence a person to death. Contrary to the belief that the condemned carried their crucifix to the site of their execution, only the crossbar was brought to the upright pole, which was set in place permanently, where it would be used for other executions. According to historian Josephus, wood was scarce in first century Jerusalem, and Romans traveled ten miles to find lumber to use for their army. According to the Biblical Archaeology Society the execution was carried out this way: Once a defendant was found guilty and was condemned to be crucified, the execution was supervised by an official known as the Carnifix Serarum. From the tribunal hall, the victim was taken outside, stripped, bound to a column and scourged. The scourging was done with either a stick or a flagellum, a Roman instrument with a short handle to which several long, thick thongs had been attached. On the ends of the leather thongs were lead or bone tips. Although the number of strokes imposed was not fixed, care was taken not to kill the victim. Following the beating, the horizontal beam was placed upon the condemned man’s shoulders, and he began the long, grueling march to the execution site, usually outside the city walls. A soldier at the head of the procession carried the titulus, an inscription written on wood, which stated the defendant’s name and the crime for which he had been condemned. Later, this titulus was fastened to the victim’s cross. When the procession arrived at the execution site, a vertical stake was fixed into the ground. Sometimes the victim was attached to the cross only with ropes. In such a case, the patibulum or crossbeam, to which the victim’s arms were already bound, was simply affixed to the vertical beam; the victim’s feet were then bound to the stake with a few turns of the rope.  Drawings of Yehohanan’s skull Drawings of Yehohanan’s skull In 1968, a Jewish tomb was discovered in Jerusalem by Vassilios Tzaferis (1936-2015), a one-time Orthodox monk. It had a Hebrew inscription which read; "Jehohanan (Yehohanan) the son of Hagkol". He came from a good family and may have been executed due to a political crime. He died some time before Rome destroyed Jerusalem in 70 A.D. The crucified man measured about 5'6" in height, which was the average for Mediterranean people and was in his twenties. His muscles indicated he never engaged in heavy physical labor, was well nourished and did not suffer from any disease. He had no trauma to his bones prior to the execution. He had a cleft right palate which deformed his teeth. His facial skeleton slanted slightly from one side to the other. The eyes were at different heights as were the nostrils. The difference extended to the lower jaw bone, and the forehead was flatter on the right side than the left.  2nd century A.D. graffiti of a Roman crucifixion from Puteoli, Italy, is one of a few ancient crucifixion images that offer a first-hand glimpse of Roman crucifixion methods 2nd century A.D. graffiti of a Roman crucifixion from Puteoli, Italy, is one of a few ancient crucifixion images that offer a first-hand glimpse of Roman crucifixion methods Later analysis of the skeleton challenged that he had a cleft palate. Seventeen skeletons from the same family were found in the ossuary. Five of the seventeen were children no older than seven years of age. Seventy-five percent had died by the age of thirty-seven; only two lived beyond fifty years of age. One child died of starvation, and a woman showed she was struck on the head by a mace. The initial assessment of the skeleton in 1970, by Nicu Haas with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem posited that the man was crucified with his arms outstretched, and his forearms on a cross. However in 1985 the finding was reappraised, where it's believed the horizontal beam was affixed to vertical stakes with the man's arms tied, and death occurred due to asphyxiation. There was lack of injury to the forearms and metacarpals of the hand, which indicated his arms were tied to the cross and not nailed there. In Egypt where crucifixion originated, the condemned was tied and not nailed. This would produce a painful and slow death by weakening the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm, where it would be impossible to breathe properly. The rarity of finding remains that demonstrated signs the person had been crucified, belies the truth of the numbers that were actually executed by this method. Ancient sources describe tens of thousands were killed this way in the Roman Empire.  Skeleton discovered close to Venice with evidence of being crucified c.2007 Skeleton discovered close to Venice with evidence of being crucified c.2007 In 2007, 25 miles southwest of Venice, a man's skeletal remains revealed a fracture of the heel bones suggesting he was nailed to a cross. He was discovered during a pipeline project. The poor condition of the bones made it difficult to be certain, and also the other heel bone was missing. There was no evidence his wrists were nailed to wood. He was buried 2,000 years ago, and the remains are the second ones that show any evidence of crucifixion. Another unusual aspect is that he was placed directly in the ground instead of a tomb, without any grave goods. A genetic test found that he was below average in height, slim and was in his early 30s when he died. The disposal of his remains and small stature, indicated he might have been an underfed slave. The lack of funeral ceremonies was part of the punishment for prisoners. The bodies of those who died by crucifixion were left to rot and be eaten by animals. In some cases, families would remove and bury the remains.  Gavello remains indicating nail was driven through the heel bones Gavello remains indicating nail was driven through the heel bones One of the factors that may contribute towards the difficulty in identifying individuals who were crucified, is the theory that nails were salvaged from the body after death. In 2021, a team excavating graves near Fenstanton in southeastern England, came across a man executed by crucifixion during the 2nd century A.D. There was a nail that pierced the heel bones during the execution. There was remnants of a wooden structure, possibly a bier. He is believed to have been in his late 20s, and lived about 1900 years ago when Britain was under Roman control. There were signs of healed injuries indicating he suffered severe trauma throughout his life. His fibula (a slender bone next to the tibia) was thinned out, which points to the belief he was kept in bondage for a prolonged time, possibly as a slave. Forty other graves were found at Fenstanton, which indicated it was used as a graveyard by the settlement. His burial was treated with the same care as others interred around him, which is opposite to those who had been executed who would be buried away from the community. DNA analysis indicated he was local to the area, but what is unknown is the reason he was crucified.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed