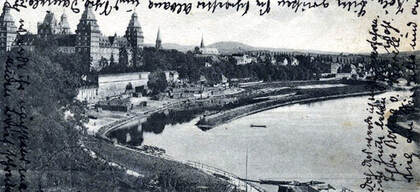

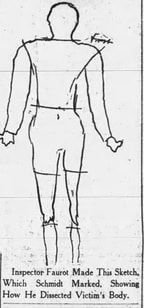

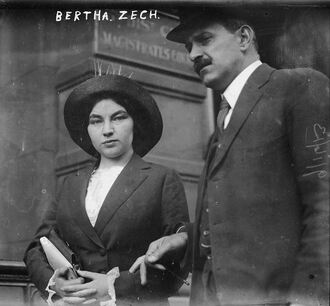

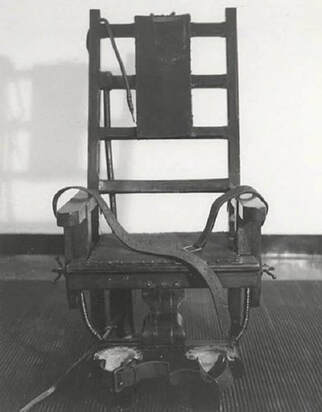

By M.P. Pellicer | Eerie.News There are persons who are never meant to hold positions of trust, and Hans B. Schmidt was one of them. Some are just untrustworthy, others are deadly.  Aschaffenburg c.1902 Aschaffenburg c.1902 Hans B. Schmidt was born in in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg; one of ten children. His mother Gertrude was Catholic and his father Heinrich was Protestant, but it was probably the beatings he received at the hands of his father that shaped the man he would become. He also witnessed domestic violence between his parents, brought about because Heinrich did not want her to practice her faith. Perhaps it was also a deep streak of mental illness that ran in his family. His father made a good living as a railroad official, but wasn't at home much. The demands of bringing up ten children proved too much for his mother, who went into a depression, and coped by attending church twice per day. The only one of her children who shared her devotion was Hans. The young Hans developed religious obsession, but sexual promiscuity with males and females as well. If this was not troubling enough, he was fascinated with drinking blood and dismemberment. His relatives described where he beheaded two geese kept by his parents, and kept the heads in his pocket. Like a moth to the flame he spent hours at the village slaughterhouse on a daily basis, where he watched animals being killed and chopped up, while he ate pieces of fruit. The slaughterhouse seemed not to sate Hans for long; chickens, rabbits and squirrels were found horribly mutilated on the farm property and the family knew it was not a wild animal. If it wasn't for the heinous act that landed him in prison later in life, none of his history would be known. But like many who prey on other human beings, their history is replete with warnings of the scourge they will eventually become to those around them. Sworn depositions from the Schmidt family filled in the blanks of his past. His older sister Elizabeth Schmidt-Schadler described his fascination with blood at a young age, as well as sexual attraction to her.  Hans Schmidt with a beard c.1913 Hans Schmidt with a beard c.1913 Han's paternal great-grandfather was institutionalized due to alcoholism. A great-grand-uncle, Jacob Schmidt was committed to an institution for his entire life and died there. Han's maternal grandfather, Andrea Seppler hung himself in 1849. In the aftermath of the suicide his uncle Conrad shot himself, however he had a history of cutting himself before the final act. Much of Han's disturbing thoughts were found in his diaries. He never tired of producing hundreds of pages detailing all his lurid experiences. When he was 19 years old he was admitted to the St. Augustine Seminary at Mainz in preparation for the priesthood. However it seemed his religious training had not rubbed off sufficiently, because in 1904 he was arrested by Bavarian police for forging diplomas for failing students. Ironically it was his father who hired a good attorney, which saved him from going to jail. The lawyer argued the charges should be dropped for reasons of mental defect. This was despite the fact the prosecutor of Mainz was intent on sending him to prison. Instead he was sent to the cold-water sanitarium at Jordanbad in Wurtenburg. He was there for a month, and only took one bath. He was then sent to Engelsburg Monastery at Miltenberg to do penance. Soon the monks tired of dealing with him, since he refused to follow any instructions. They sent him back post haste to the seminary at Mainz. In 1905, he followed the highly-publicized murder case of Harry Thaw. His sympathies lay with the killer, and thought he was being persecuted. Perhaps Thaw was right in killing Stanford White he surmised. It was apparent there was something wrong with Hans Schmidt, both morally and mentally, or perhaps in present day vernacular he was a psychopath. He said that he was ordained by Bishop George Kirstein on December 23, 1904. However conversations he had later in life with alienists, as psychiatrists of the day were called, seemed to reflect that an ordination with a vision he had of St. Elizabeth was the one that counted, at least in his mind. He described it this way: The Bishop ordained me alone. I do not like to speak of it. The real Ordination took place the night before. St. Elizabeth, she ordained me herself. I was praying at my bedside when she appeared to me and said, 'I ordain you to the priesthood.' There was light during her appearance. I told no one. I thought it best to keep it to myself. They would make fun of me. They always made fun of me for these things. They always expect others to do as they do. God speaks to different people in different ways.  Anna Aumuller Anna Aumuller He never explained why the Bishop would ordain him alone, at midnight in his room, but most probably it was because many in the seminary thought Hans was not priest material. He was assigned to the villages of Burgel and Seelingstadt, where he cut a wide swath of immoral acts with the those who lived there. He molested altar boys, kept company with prostitutes and had sexual liaisons with women. Schmidt gave sermons that were so strange that not only did the other priests complain about him, but parishioners as well. The bishop and monsignor were in a quandary; they couldn't keep him there, but no other parish would accept him. Whether by his own decision or the diocese in Mainz, by 1909, Schmidt then 28, was sent to the United States, and assigned to St. John's Catholic Church in Louisville, Kentucky. Trouble soon brewed between him and the senior pastor, and he was sent to St. Boniface's Church in New York City. Later rumors surfaced that Schmidt had been defrocked and banished in Germany. He had gone to America presenting his ordination papers to the church superiors first in Louisville, then Trenton, NJ and finally New York City, without mentioning that he was no longer a priest. Three years passed, and it was in the rectory of the St. Boniface church that he crossed paths with Anna Aumuller the housekeeper. She had immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1910, when she was 18 years old.  Bishop Georg Heinrich Maria Kirstein, the Roman Catholic bishop who supposedly ordained Schmidt to the priesthood in Mainz, Germany, on December 23, 1904 Bishop Georg Heinrich Maria Kirstein, the Roman Catholic bishop who supposedly ordained Schmidt to the priesthood in Mainz, Germany, on December 23, 1904 Like his later disclosure about his ordination, he told alienists that he heard a voice, which he believed to be God telling him to "love" Anna. She resisted the advances of a priest who was ten years older than her, but eventually she became his mistress. In a pattern followed by his superiors at his prior posts who did not know how to handle the strange reverend, he was reassigned to St. Joseph's Church in Harlem. He continued in the secret relationship with Anna, and at the same time had a homosexual affair with Ernest Muret with who he was running a counterfeiting operation. Anna was fired from St. Boniface after it was suspected she was pregnant, and by none other than Father Schmidt. Perhaps to quiet Anna who faced ostracization not only by the church but by the community, he performed a marriage between them, including filling out a marriage certificate. He told her he was leaving the church for her.  Sketch of how Schmidt dissected Anna's body Sketch of how Schmidt dissected Anna's body Schmidt would go on to desecrate the high altar at St. Joseph Church by having sex with Anna on it. He said that God repeatedly told him to "sacrifice" her. Apparently he told Anna about his impulses, and she called him crazy, but she was bound to him more than ever since she was pregnant. They went on to rent an apartment even though he continued in his double life. On the night of September 2, 1913, he cut her throat with a 12-inch butcher knife while she slept, drank her blood, and raped her as she died under him. Later he dismembered her body using a hacksaw and the knife. First was her head, and then he cut her in half, wrapping each section in a newspaper dated August 31. The lower part was in a pillowcase monogrammed with "A" on it. He threw gray-green schist inside the pillowcases to weight it down. He boarded the Fort Lee ferry seven times, and threw the pieces into the Hudson River. For Schmidt it was business as usual. He returned to the church, performed Mass and gave Holy Communion to the parishioners.  Hans Schmidt and Ernest Muret Hans Schmidt and Ernest Muret It seems the rocks didn't weigh the body down enough, and on September 5, two children found the upper torso of a woman at Cliffside Park. Three miles away in Weehawken, New Jersey, the rest of her came ashore, minus the head though. Eventually other grisly finds were made. The autopsy estimated the woman was in her 20s, was about 5'4" tall and weighed about 125 pounds. It revealed she had given premature birth just before she was killed. Eventually the coroner would sew together six pieces of a body that had once been Anna Aumuller. Her head was never found. The first clue Hudson County police found was a price tag attached to a pillowcase wrapped around the body part. It was traced to a factory in Newark which sold only to George Sachs, a furniture dealer in Manhattan. Then New York City Police Department took the case and assigned detective Joseph Faurot to it. Faurot visited George Sachs at 2782 Eighth Ave, but the furniture dealer couldn't remember how many pillow cases he sold. A check was made of his receipts, and there was a sale of a bedspring, mattress, pillow and pillowcases on August 26, 1916. The buyer was A. Van Dyke and the items were delivered to 68 Bradhurst Avenue, to a 3rd floor apartment. The building superintendent told them a married couple had rented the apartment two weeks before. He described the man as speaking with a thick German accent, and his name was H. Schmidt. The police watched the building, but no one came to the apartment. Eventually the police forced the door and examined the interior. They found the floor was scrubbed, but there was dried blood splatters on the walls. Inside a trunk they found the saw and the knife. There were also handkerchiefs with an embroidered "A" like the pillowcases. They found clothing with a label of A. Van Dyke sewn into the lining. There were letters in both German and English addressed to Hans Schmidt. Later it would be revealed that it was Anna who had embroidered the A into the bedclothes that would eventually lead to her killer.  Chief of Detective Joseph Faurot Chief of Detective Joseph Faurot Many of the letters originated from women in Germany, however most of them were from Anna Aumuller with an address of 428 East Seventieth Street. Inspector Faurot and detectives Cassassa and O'Connell went to the address, and found that Anna had moved after being hired as a housekeeper at St. Boniface's Church. This was their next stop, and the senior pastor Fr. John Braun said Anna had been his housekeeper, but had transferred to St. Joseph's Church. They asked him if he knew Hans Schmidt. Father Braun said he was a priest who had once served there, but had been transferred to St. Joseph's Church as well. The police finally found their man. It was after midnight when Father Daniel Quinn took them to Schmidt's room. The priest quickly admitted, "I killed her! I killed her because I loved her!" He went on to describe how he murdered her, and what he did with the body. Father Quinn listened in horror. Once arrested the archdiocese of New York suspended him. Considering he had confessed, his defense team argued that he was insane and presented his bisexuality and hearing voices to prove their claim.  Ernest Muret escorted by Detective McKenna c.1913 Ernest Muret escorted by Detective McKenna c.1913 Dr. Smith Ely Jeliffe, a psychologist testified that Schmidt should be spared the death penalty since he had up to 60 relatives who displayed signs of mental instability. Dr. Jeliffe said, "On one occasion he had taken the head of a rooster and put it while still bleeding on the end of his penis, and had walked around strutting about with this decapitated head of this rooster on his penis, until his father caught him and beat him." When he was 10 years old, Hans started a sexual relationship with a neighborhood boy named Fritz. They continued having sex for years. They both went to the slaughterhouse and would become sexually aroused with the sight of blood. During that period, Hans also began to have sexual relations with his older brother, Karl. Other alienists who interviewed Schmidt before his first trial, testified for the prosecution that despite Schmidt's story about hearing voices telling him to "sacrifice" Anna, he was completely sane.  Bertha Zech during the Schmidt trial c.1914 Bertha Zech during the Schmidt trial c.1914 On September 16, 1913, Dr. Ernest Muret was arrested for his part in the counterfeiting scheme. The apartment where they ran the operation had been rented using the name of George Miller, which was an alias used by Muret. The pair had told renting agents they were medical students that were going to use the flat for experiments. Authorities found plates for $20-yellowbacks which seemed to have been made by an expert engraver. They also found $10 false bills. Muret told police he was born in Chicago, and received his dental certificate in 1911. He said he had studied abroad for 14 years and had been a student at the Berlin Dental College, but had not passed his examination and didn't receive a diploma. He returned to New York in 1903, and served as an assistant to other dentists before opening his own office two years before. Muret was convicted in October, 1913, of counterfeiting charges and sent to the federal prison at Atlanta to serve a 7-year sentence. It turned out he was never a dentist, but he was not prosecuted for this.  Electric chair at Sing Sing Prison Electric chair at Sing Sing Prison In December, 1913, the trial ended in a hung jury of 10 to 2. Two of the jurors seemed to be swayed by the argument that Schmidt had killed Anna because he was insane. Two weeks later, the second trial began, and the prosecution brought in a new witness. Her name was Bertha Zech, a fellow German immigrant who said that in April 1913, before Schmidt supposedly heard the voices, she posed as Anna Aumuller and purchased a $5,000 life insurance naming Father Schmidt as the sole beneficiary. Bertha worked for Muret as a maid at his office. It came to light that Schmidt and his lover planned a series of murders and insurance frauds, and had blank death certificates ready to be falsified. On February 5, 1914, it took the jury only 3 hours of deliberation to find Schmidt guilty of first degree murder. After being sentenced to death he said, "I'm satisfied with the verdict. I would rather die today than tomorrow." He was sent to Sing Sing Prison. While he was in the Tombs awaiting execution, Schmidt declared that he was planning to do away with the hopelessly insane, the permanently crippled and those suffering from incurable diseases by poison or by the knife. As was expected Schmidt's attorneys filed an appeal and stayed his execution for one year. In December, 1914, Schmidt confessed to feigning insanity, but said Ernest Muret his homosexual lover had accidentally killed Anna during a botched abortion. His love for Muret had made him take the blame for the crime.  The apartment building where Anna was killed c.1913 The apartment building where Anna was killed c.1913 The ploy didn't work, and Schmidt went to the electric chair on February 18, 1916. His last words were, "I want to say one word before I go. I beg forgiveness of all I have offended or scandalized, and I forgive all who have offended against me!" Then before the switch was thrown, and he had the hood over his face he said, "My last word is to say goodbye to my dear old mother!" Newspapers had been avidly following the story. A reporter with the Albany Times wrote, "His last night on earth he spent proclaiming his innocence and declaring that he had made peace with God. The guards had expected a scene when the slayer was to be executed. But his actions surprised them. He was the coolest man in the death chamber. He almost domineered those who assisted in putting him to death." Schmidt was interred by Father William Cashin in Sing Sing's cemetery since his body couldn't be sent back to Germany because of WWI. The Schmidt family asked his burial location to be kept secret. Even though other crimes were never proven against him, he was a suspect in several cold cases. He kept company with a woman named Helen Green, who left to Chicago a month before Anna was murdered. Helen Green was never found, in New York or Chicago. It's thought he did away with her. There was another woman Schmidt was seen with, soon after his arrival in America that he said was his wife. She also disappeared.  Alma Kellner an 8 year old girl murdered some believe by Hans Schmidt and not Joseph Wendling Alma Kellner an 8 year old girl murdered some believe by Hans Schmidt and not Joseph Wendling Schmidt's attorney recalled a conversation with his client, he said, "He admitted that he had taken a small boy to an apartment at 124 West Eighty-fourth Street, but denied that it was his son. He said he wouldn't tell who the boy was because he didn't want to drag his family in. 'As for the girl, Helen Green for whom the police are looking for,' Schmidt said that he had met her casually and described her as a 'girl of the streets'." This coincided with a story told by another person, which led authorities to believe it wasn't only women he killed. The owner of the apartment building where he lived said that she saw him sometimes bringing a 5-year-old boy to his room. He said the boy was his son, but one day he disappeared. When the landlady asked him the name of the boy he said it was August Van Dyke. Police had found a letter from Helen Green who wrote Schmidt that she could not live without him. It was believed she was in Chicago, but after her disappearance a month before, no trace of her could be found. She had met Schmidt the winter of 1912. Once Schmidt's photograph was publicized many recognized him as the man frequently seen along the Great White Way, which was how Broadway was known in those years, enjoying the night life. He represented himself as the "Count" and the son of noble persons.  Wendling convicted of killing Alma Kellner was paroled in 1935 and deported to France Wendling convicted of killing Alma Kellner was paroled in 1935 and deported to France Schmidt was also a suspect in the murder of Alma Kellner, 9, whose body was found buried in the basement of St. John's Church in Louisville. On December 8, 1909, she left her home at 507 East Broadway in Louisville to attend mass at St. John's Church. She was wearing a brown, plaid dress with cream velvet trim and collar. Over this she wore a dark brown coat and a red hat. It was the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and solemn mass was planned. This was six blocks from her home. She failed to return and by the afternoon her family notified police. The force scoured the city looking for her, and hospitals were contacted to see if a child fitting her description had come into their care. As the hours passed and no clue was found, authorities theorized she might have been kidnapped since the family was well off. The weeks turned into months, and no ransom note was received by the family. On May 26, 1910, the custodian of St. Joseph's school found the basement was flooded almost four feet due to a broken pipe. Four days later a plumber found that a bad stench pervaded the basement once the water level had dropped to one foot. As he started to clear out the debris with a shovel he struck something just under the water. From the light of a lantern he saw a small foot and shoe sticking out from the rubbish. Ten minutes later the police arrived and soon confirmation was made that Alma Kellner had been found. Her body was wrapped in a carpet. When the coroner touched the carpet, flesh fell from the bone. The right foot was missing from below the knee and both hands were gone. Most of what was left was skeletal. Her skull was fractured in several places and pieces of the cranium had broken off. Some of the bones were charred. Father Schuhmann, the pastor at the church did not know the cellar even existed until the problem arose with the broken pipe. The police theorized that whoever brought her there knew of the place beforehand, since its existence was not common knowledge. Inside a closet police found a remnant of a carpet that matched the one she was wrapped in. This was the closet used by the janitor. They also found a bloodstained, man's shirt inside. The school janitor Joseph Wendling had been questioned when the girl disappeared in December, and walked off the job the following month. His wife Lena Wendling, still lived on the school grounds in the janitor’s apartment. She told police he had a history of leaving his job without any reason. Wendling had been hired at the church in November, 1909, and he had keys to all the buildings on the property. Wendling went from state to state, until a detective from Louisville caught up with him in California. This was 3 months after the discovery of Alma's body. He kept insisting he had not killed the little girl. By December he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Alma's uncle requested that Wendling should be pardoned and deported to France his country of origin in 1935. He served 26 years in prison for the crime, and claimed he was innocent until the day of his death. When Schmidt was asked about the Kellner girl, who was killed during the time he was posted to St. Louisville he said he had never heard of her. This was strange since the crime had made the front-page news, and she was a student at the Catholic school he visited in 1909. Considering the child's body was found only a few feet away from the altar, the diocese cooperated with the authorities, so it would be difficult to believe he was not familiar with the girl. The notoriety of Schmidt's crimes in the United States, led German police to trace evidence of a murdered girl in Schmidt’s hometown of Aschaffenburg back to him. The Germans never had a chance to question Schmidt before he was executed in the United States, and the case went cold. Faurot gave a chilling description of Schmidt for a New Zealand newspaper in 1913: "He has been characterized by some as an 'arch demon.' I should prefer to designate him a monster for most certainly he is the most monstrous creature that ever confronted me in my long connection with the police." Source - The Buffalo Evening News, Daily News Sun, Star Gazette, The Courier Journal

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed