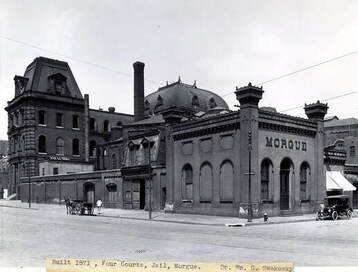

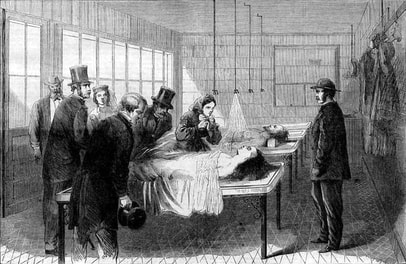

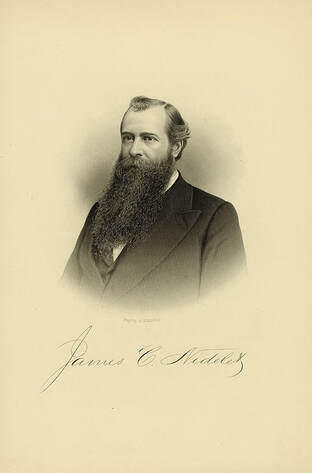

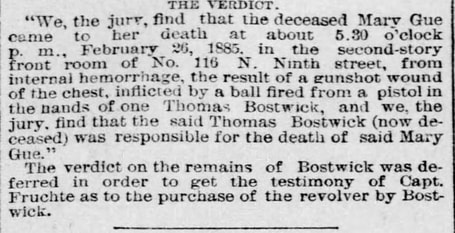

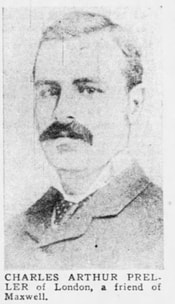

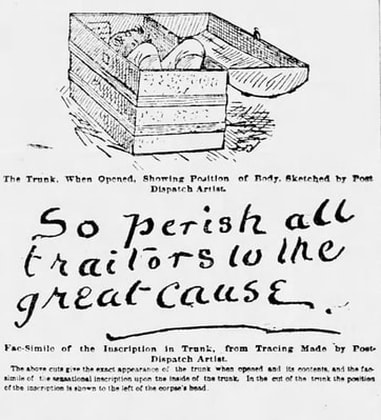

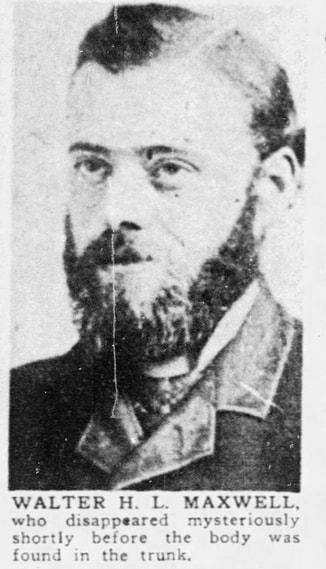

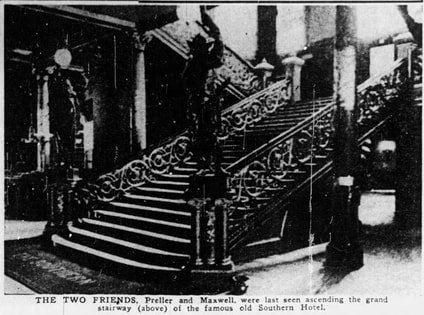

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories "My first night in the morgue I shall never forget — in fact, the first month was so full of horrors I wonder how that I ever got through it."  St. Louis morgue at Four Courts St. Louis morgue at Four Courts 1887 A morgue superintendent told of his times working at the St. Louis morgue. It's believed the source of the stories was Herman Praedicow (1831-1891), even though he was interviewed anonymously. He spoke of a prior morgue superintendent who lost his job with a change of administration, but he used to come down every day and hang around looking at the bodies. One night he took a dose of cyanide of potassium, and sat down at his table to describe how it felt to die. He'd only written a few sentences when he fell over dead. His spirit was said to haunt the morgue. The coroner told that one of his first cases was searching through the pockets of a "floater", laid out in a pine box which was already dripping slimy ooze, making a slippery puddle underneath it. The body was already starting to smell. He got the job in the summertime when the morgue became full of "floaters" and those who had succumbed to the heat. He had to stay on the premises all night long to receive bodies, and to deliver them to friends or family.  Victorian Era morgue c.19th century Victorian Era morgue c.19th century In between deliveries he would take naps on a lounge area in the back. Upon a shelf were 2 or 3 infants pickled in alcohol, and a man's heart with a knife blade in it also sat sealed inside a jar with alcohol. The gas jet flickered on the jars and he thought he could see those infants grinning at him, and their chests seemed to move with breath. The heart appeared to palpitate. Then he heard a strange clacking, crunching noise like teeth hitting each other. He looked at a skull on a shelf above him. Then suddenly one of them moved, the jaws moving, and something flashed behind its eyes. It sat on the edge of the shelf, and then it fell to the ground, landing on a feather duster. It rolled towards him and the clacking continued. He grabbed it and a large insect flew out. Eventually he learned to overcome his nerves and sleep when the chance presented itself. However he was awakened two or three times by explosions. He would go to the dead room, to find that one of the floaters had burst and splattered the walls, causing him to slip as he trekked across the floor. Other times the rats would get in among the coffin full of bones, and make a horrible clatter. What else was there to do except to drive them away. Every once in a while he would hear the sounds of talking in the dead room. He'd look and see forms of men in the gloom. When he turned on the light, they were the clothes of the "unknown dead" hanging on the wall for identification.  Dr. James Nidelet served as a physician for the St. Louis morgue, performing autopsies Dr. James Nidelet served as a physician for the St. Louis morgue, performing autopsies He witnessed the medical examiner completing many autopsies, which were performed by Dr. James C. Nidelet (1833-1910), who was Chief Surgeon under General Price in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, before coming to St. Louis. In 1885, the morgue superintendent received the bodies of Tom Bostwick, 36, a saloon keeper and Mamie McGue, whose real name was Mary Guerin. Bostwick killed himself at Madame North's, a well known brothel. The immediate cause of death was a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was cut on his hand and five times in the body, which indicated perhaps his victim had tried to defend herself. The story told of what led to the crime, was that Mary Guerin asked for a downstairs room when they arrived at Madame North's, but Bostwick insisted on going upstairs. It appeared he suspected she would try to escape from the murder-suicide plot he had decided to carry out that day. Mary claimed she was about 27 years old and married to a man who worked at Hilton's restaurant. She had come to St. Louis about 1881, and worked at Mollie Hines' house. The coroner had referred to her as an "outcast" which was a euphemism of the times for a prostitute. Once a man came from Illinois with a requisition for her arrest on the charge of stealing silverware. She was arrested and given over to Mr. Carroll who came on behalf of the Springfield courts in Illinois, and who claimed to be related to her by marriage. Mr. Carroll ran out of money before he could get her back to Springfield, and she returned to St. Louis where the police declined to re-arrest her. Amidst the scandal Bostwick's wife arrived from Cincinnati and identified her husband at the morgue. She confirmed her husband was a barkeeper by trade. He had told her that the woman, referring to Mary Guerin, insisted on pursuing him and that she was the cause of all his troubles. He had never mentioned he would kill himself.  J.B Guerin who was married to Mary Guerin arrived at the morgue, and was very mournful. He testified he had been married 15 months, and that his wife had complained that Bostwick threatened to kill her because she wouldn't marry him. He had known her as a widow by the name of Mrs. Goodwin, when in reality it was Edwards, and she was no widow. She had always behaved as a good wife, and he had no idea she was living a double life, and being unfaithful with a saloon keeper she knew from her days as a prostitute. Bostwick was also known to have beaten Mary several times. Lizzie Bostwick was described by the coroner to have stared at the dead Mary Guerin with intense hate. When asked if she would bury her husband she said, "No, those who got his money can bury him. I will not." The coroner's inquest arrived at the following verdict: We, the jury, find that the deceased Mary Guerin came to her death at about 5:30 o'clock p.m. February 26, 1885 in the second-story front room of No. 116 N. Ninth Street, from internal hemorrhage, the result of a gunshot would of the chest inflicted by a ball fired from a pistol in the hands of one Thomas Bostwick, and we the jury, find that the said Thomas Bostwick, (now deceased) was responsible for the death of said Mary Guerin.  Arthur Preller was found nude and stuffed in a trunk at the Southern Hotel in St. Louis c.1885 Arthur Preller was found nude and stuffed in a trunk at the Southern Hotel in St. Louis c.1885 Through the years, the coroner had seen family members come and take a deceased person for burial, which they had not seen for years. He witnessed women fight like tigers over the corpse of a dead man, who in life was not worth his salt. Some men came to claim a woman's property, but never bury a woman to who he had been "attached by any of the ties unrecognized by the law." People would visit for days and days, and you could tell by the way they acted they were afraid, yet anxious to find someone for whom they were looking. There was another time when the coroner was sitting on the steps, and a man came up to him. A woman had just left after asking him about the bodies. The man asked, "'Know that woman?" "No," the coroner replied. The man said that he was following her, and "If I find anything out, you'll have her here tonight." He left. Two hours later the woman was brought to the morgue dead. The man had kept his word for he shot her in their home on Gratiot Street. His name was Milton Neal, and her name was Nettie Hayden. She was 29 years old when she died. It seemed jealousy motivated the murder. Each of them were married to other people, but had been living together for five years and produced five children. Neal was charged with second degree murder for shooting his mistress, and in 1887 was sentenced to 10 years in the penitentiary. He had worked as a car porter at the Pullman Palace. Neal had testified at his trial that he had shot her accidentally after she attacked him, however Nettie's 10-year-old son Haggie Hayden, said he saw Neal push his mother behind a door and shoot her.  The circumstances of the Preller case made headlines across the country The circumstances of the Preller case made headlines across the country Dr. Maxwell Lennox was described as a "dude from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head." He wore his hair banged like a girl. His manners were very effeminate, which he even carried so far as to walk with short, mincing steps like a woman. Before eating he would arrange his hair, touching it up delicately and puffing out the curls. He was seen in the company of Charles Arthur Preller for several days at the Southern Hotel in St. Louis for several days. Then Preller dropped from sight. What had led to the discovery was a foul smell coming from Room 144. Three pieces of luggage were found there, but it was a certain trunk which had the odor coming from it. By then Dr. Maxwell Lennox had disappeared, however upon opening the trunk they found out where Preller had gone. His mostly nude body was stuffed inside; he was wearing drawers too small for him embroidered with the initials H.M.B. Tacked to his head was a message that read, "Thus perish all traitors to the cause." Later it was determined that Maxwell had left the note on the body, in an effort to paint the murder as the hand of some secret society. According to the coroner, the body had been in the trunk for almost 2 weeks. His tongue was protruding, he had large blisters on both legs, and a cross carved into the flesh on the breast. Later it was discovered he had died from chloroform that had been purchased by Dr. Maxwell. The coroner injected embalming fluid into Preller so that his features would became recognizable, since decomposition had made him unrecognizable. The motive for the crime was robbery.  Hugh Mottram Brooks AKA Dr. Walter Lennox Maxwell killed his companion and stuffed him in a trunk c.1886 Hugh Mottram Brooks AKA Dr. Walter Lennox Maxwell killed his companion and stuffed him in a trunk c.1886 By the time the body was discovered Maxwell had left St. Louis, however in his haste he left many clues behind. Most had been useless items that belonged to Preller, however he did leave information as to who he really was. His name as well as his title of doctor were fictitious. Based on information police found in the room, his true name was Hugh Mottram Brooks. He took $700 cash, jewels and valuable papers from the victim. The authorities learned he was heading to San Francisco, where he would take a ship to Auckland, New Zealand. He traveled as T.C. D'Auguier, and when he arrived in San Francisco he posed as a Frenchman. Initially he shunned attention but he couldn't overcome his "peacock tendency" and became the focus of many eyes which "seemed to suit his vanity." Unknown to him, while he sailed the story of the murder had been written up in newspapers around the world. Police were waiting for him on the dock in New Zealand. Detectives from St. Louis traveled there to bring him back. During the trial Brooke claimed he was treating his friend for a "private disease" and accidentally used too much chloroform. The jury didn't believe him, and he was found guilty. Even when his parents Samuel and Hannah Brooks, asked for clemency from the governor, there was no reprieve. On August 10, 1886, he was hanged at the Four Courts with 200 witnesses in attendance. This was right next to the morgue.  The Southern Hotel, St. Louis, where the two companions were last seen before the murder The Southern Hotel, St. Louis, where the two companions were last seen before the murder According to the coroner the worst bodies to handle after the floaters were those of victims of railroad accidents, who were mangled and torn to shreds. One man who was struck by a train near the cemeteries and dragged about 400 yards was brought in a barrel. There was nothing in the "horrible heap" which could be recognized as the remains of a human body except for a little finger. He was never identified. Another man who was run over at the mouth of the tunnel, had his head cut off at the shoulder clean as if it was done with a knife. He dressed the body and sewed on the head, and hid the stitches with a high standing collar and dressed him nicely. He was sent home looking as if he had died in bed. There were times when he used wooden sticks where the bones had been torn out, and fastened flesh around the sticks. Sources - St. Louis Globe Democrat, St. Louis Star and Times, St. Louis Star Dispatch

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed