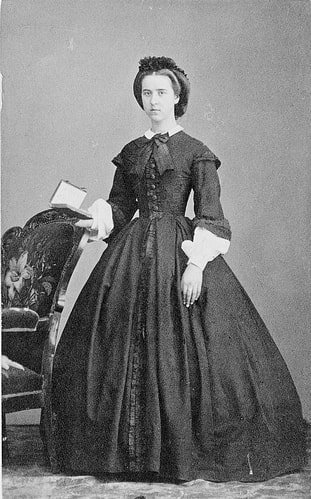

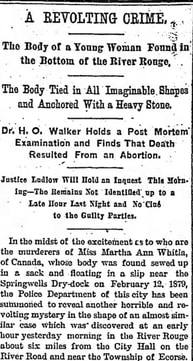

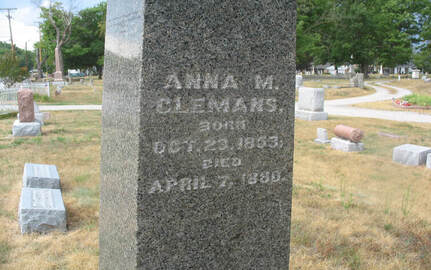

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories On a frigid, winter day in 1879, a burlap sack floated underneath a vessel at the Springwells dry dock. It turned out to be the burial shroud of woman who was bound and gagged.  The woman's identity was a mystery for more than a year. The woman's identity was a mystery for more than a year. The woman's body was well preserved by the icy waters of the Detroit River. V. Giest & Son's Undertakers allowed the public to view the girl, hoping someone would know who she was. A description of the body, her clothing and the articles in her pockets were listed and sent to the surrounding towns, hoping to solve the mystery of her death. At one point, it was thought she was a woman known as "The Spanish Doctoress." However this woman turned up very much alive and living in Ludington. The authorities followed different leads, but none produced the name of the woman. More than a year passed, and not until April 1880, did authorities determined through different clues that her name was Martha Ann Whitla, whose parents lived in Canada. They had believed she was still alive, even though she had disappeared from their view. Their description of her person and her clothing closely matched the dead woman, and that her disappearance from home coincided when the remains were found in the river.  Michigan farmers c.1889 Michigan farmers c.1889 It came to light that she once lived at the home of John Theis in Dearborn. Then the investigator said the woman's real name was Martha Pugh, that she was born in Ohio, and John Whitla adopted her after the death of her parents and moved to Detroit. Martha worked at different places in Detroit usually as a housekeeper. She worked for Hugh S. Peoples, Abner Tattle and John Theis. It turned out that one of the Theis sons had become enamored with her and wanted to marry her, and she corresponded his affection, but his father objected, and there was suspicion that the family had taken "foul means" to prevent the marriage." The Theis family were farmers. Mr. Theis, Sr. among the outrage of having sons arrested, insisted there was only personal friendship between Miss Whitla and his son Henry, and he would not consent to any of his sons marrying a French, American or Canadian girl. They had to marry a German girl since this was their nationality. Amidst the excitement of the Whitla murder another body was found in the River Rouge.  Isolated farmhouse on the River Rouge Isolated farmhouse on the River Rouge The night was damp and windy on April 6, 1880, when the Cicotte family sat around the crackling flames in the fireplace that warmed the home where the family had lived for 52 years. The house faced a remote stretch of road, and considering the weather and the time of day, the family paid attention when they heard a buggy pass so rapidly, they believed the horse had run away with the vehicle. When the buggy came to the bridge over the Rouge, it stopped. A quarter of an hour later, the buggy came back, the horse again moving along at a clipping rate. This time Cicotte's son went out to see who it was, but the rig disappeared in the darkness of the night. The next morning, two men, Martin and Solo were passing along the road heading into the city. On the west side of the bridge, they found wheel tracks in the mud indicating where someone made a turn in their rig. They examined it, and then returned to the bridge to keep on their trip. Then one of them saw on the south side of the bridge, suspended on one of the timber braces, a woman's cloak. They brought the cloak up and were horrified to see it was stained with fresh blood. They also found a lump of hair clinging to it. They went to the closest house, which was the Cicotte residence, and gave them what they had found. The cloak also had strands of white horse hair. The garment was well made and had a hood trimmed with silk.  South Bridge over River Rouge South Bridge over River Rouge Superintendent Rogers who had been investigating the Whitla murder was told of what had occurred. The authorities dragged the river in the vicinity of the bridge. The area above where the cloak was found was about 20 feet deep and very muddy. Soon after they started, they caught a heavy object which was resting at the bottom of the river. It was the body of a woman, and it had a common limestone attached to it which weighed about 40 pounds. The body was tied with knots in all "manner imaginable." The hands were securely tied at the wrists and crossed over her chest. Her legs were tied together, and a line had been passed under her knees and over her head, drawing her head down to her knees. The body was taken to the office of Justice Ludlow who impaneled a jury. It was laid out on two rough planks to be inspected by all the jurors. The woman was described as being in her twenties. Her face showed the effects of being in the water, "her nose being drawn up and her eyes and mouth partially open. The skin was drawn together. Her head was covered with thick brownish black hair, done up in a cord fastened with two brass hair pins and several black pins." Her undergarment was saturated with blood. "Her dress was black, her stocking were of balmoral, striped with black, brown, red and other colors. She wore nearly new pebble goat shoes laced on the side." She had small feet and hands. Later a large sized basket was found on the shore of the river near the bridge. It was new and wet, and the sides were pressed in. Some believed the body was packed inside after it had been tied up. A bottle of medicine was found afloat in the water, but it was unknown if this belonged to the victim. A post-mortem by a doctor found a small hole directly above the right ear, but it was only a bruise. There was no damage to her brain, however the upper portion of the body was terribly bruised. There were no traces of cut, stab or shot wounds, however it was found that some internal organs were very inflamed, and the doctor concluded she had died as result of an abortion. He declared she was thrown into the river shortly after her death. The body was sewn up, placed in a rough box and brought to the undertaker on Monroe Street. It was Valentine Geist & Son's, the same undertakers that received Martha Whitla's body. Like Martha's body, the undertakers laid the body on ice, and hundreds visited during the afternoon, but still she was not identified. Some believed she was a prostitute who worked in a brothel in the city, and after her death was brought out and thrown in the river.  The horrible circumstances of these women's death outraged Detroit. The horrible circumstances of these women's death outraged Detroit. A Mrs. Osmun came to the police, and said she believed the woman was someone she had recently met. The woman claimed she had some trouble with her husband and was going to the law about it. Mrs. Osmun said the woman had been driven in a buggy by an unknown man, who during the ride made improper proposals to her, and she decided to walk back to her home. The woman told Mrs. Osmun she had a child who was staying with friends on 17th Street. When they reached a saloon opposite the Fort, she gave Mrs. Osmun some money to buy beer. Then Mrs. Osmun spied a certain man who lived in her neighborhood. She refused to go into the saloon and promptly returned the money; after which she left. Mrs. Osmun never got the woman's name. Then a man with the name of "Jomio, Dromo or Moro" who lived in Delray said he saw the dead woman the past Sunday at the fort in the company of another woman. Finally, the identity of the man who saw her was found to be a laborer who lived in a brick cottage several streets below the Justice's office. The man's name was Julius Gagnier. This corroborated Mrs. Osmun's story. He told the detective the other woman was a certain Mrs. Osmun who kept a small notion store. He made the following statement to the police: I was near the Fort last Sunday afternoon and saw two women go into a saloon and ask for a drink. The barkeeper refused to grant their request and one of them remarked, 'We will go elsewhere.' They both left and started away. One of the women wore a cloak which I am satisfied was the same as the one found on the bridge; and furthermore, if I was up on the stand, I would swear that, to the best of my knowledge and recollection, the woman they found in the river was one of the two. I am quite sure of it. She was of the same size, and to my nearest recollection she looked just like her.  Detroit streets c.1890s Detroit streets c.1890s The detectives went to the saloon Gagnier told them about, who corroborated his story, but he thought both women had worn shawls, and not a cloak. By April 15, the identity of the women tied to the stone became known. Her name was Anna "Annie" M. Clemans from Bay City. A chain with a locket containing the picture of her fiancée, a gentlemen with who she had "kept company" for years, and some very fine rings were missing. Within a day, arrests were made in both cases. Dr. William G. Cox and Henry W. Weaver were brought in for complicity in the death of Annie M. Clemans. Harriet Snyder (Schneider) the madam of a brothel at No. 7 Porter Street where it was alleged Annie Clemans met her death was arrested as well. At their arraignment it was stated that Annie was forcibly drowned, but she had also been the victim of a botched abortion.  Bay City lumber yard, c.1880s Bay City lumber yard, c.1880s The trial for the Clemans case started at the end of May, 1880, for Henry W. Weaver and Dr. William G. Cox. Belle Wagner, 16, testified that she worked for Mrs. Snyder as a housekeeper, and confirmed that the dress belonged to a young woman who she had seen once at the house. During the next few days the woman stayed in one of the rooms. She complained of a headache and pain. She sickened more and started to vomit. Then she saw Dr. Cox coming to call and check on her. She had seen the lady the day before the body was found in the river. When she asked Mrs. Snyder about her, she was told the lady got well and went to Chicago. Annie's mother, Abigail Clemans said she had met Thomas D. Merritt about five years before. She stated he was a constant visitor at their house. Merritt had given Annie the chain, locket and the rings that were missing. The last time she had seen her daughter Annie showed her mother $25, which she said Merritt had given to her for a purpose, and that she was going to Norris to visit a friend. Annie's father, Isaac T. Clemans was a station agent of the Detroit, Bay City and Saginaw Railroad at Reese Station. Like his wife, the last time he had seen his daughter alive was March 31. Mrs. Snyder testified that she had met Annie when she came to her house, and that Dr. Cox had attended her, and that she had miscarried one of the nights she was there. She lingered a few days than died in Mrs. Snyder's bedroom with Dr. Cox in attendance. The doctor left and returned around midnight and she helped him put her clothes on. Dr. Cox then looked through her valise to find out her identity. Mrs. Snyder told him she didn't want to know who she was. Some letters found in Annie's hat were burned. She insisted that they needed to let her family know what happened to her. She said, "he replied it would be best not to, as it might get them all in trouble." He returned the next day, and the body remained in her room. She helped him take the body to a shed in the back of the house, and they put it inside a basket. Later that night she stayed in her house, and heard someone walking in the shed and the noise of a wagon in the alley. She had given Annie's chain to her daughter, and thrown the rings into the St. Lawrence River.  Grave of Anna Clemans Grave of Anna Clemans On July 4, 1880, Dr. Cox was found innocent of the murder of Anna Clemans, as was Henry Weaver, a furniture repairer who helped in transporting and dumping the body. In January 1882, the story took a weird turn when the police arrested Dr. William G. Cox and Harriet Snyder for the murder of Martha Whitla. The charge was that Martha had also died of a botched abortion carried out by Dr. Cox at Mrs. Snyder's house. The charges were dropped a month later, and new persons were charged. It was Hugh S. Peoples and Dr. James N. Hollywood who were accused. One witness testified that Martha knew Hughes from before his marriage, and that he had seen them talking together after his marriage in the yard and in the barn. He had seen her go to the barn where Hughes was several times, even though by now he was a married man. It was not known where Mrs. Peoples was at these times. During the trial, evidence was entered that Elberta L. Kimball had tried to blackmail Hughes. The basis for the blackmail was that he owed Martha $400, and if he didn't meet her demands she would inform The Evening News. The threat was based on the $400 debt being a motive to kill Martha. Later, Miss Kimball denied she had ever written the letter. During the trial, Dr. Cox testified that he was slightly acquainted with Dr. Hollywood, and had never called him into consultation. Hollywood (sotto voce) said, "That's a lie!"  The case against Dr. Hollywood was dismissed The case against Dr. Hollywood was dismissed Another witness was a man named Frank de Rice. He described where Hughes approached him asking that he marry a lady friend of his for $50. The next day he met her, but she used the name of Mary Brown, and he used the name of Charley Clark. They went walking alone and told each other their real names. Hughes then told de Rice, the $50 was a down payment, and when they married he would send $300 in 3 semi-annual installments. De Rice weakened on his intent saying he didn't fancy Martha, and instead of meeting her went to Pontiac. After going away for some time De Rice met with Hughes again, who told him that the "girl had got him into a pretty hot corner and things had taken a change." De Rice then met Dr. Hollywood, who told him all he had to do was take out some baggage, and that it would be in a trunk. At that time Martha was alive, and Hollywood said that he would disfigure the face so she couldn't be identified. They want De Rice to dispose of the body somewhere in the country or in the water. While De Rice was waiting for a notice from Hughes, he had gone to Rochester and opened a shop. The defense posited that Annie Clemans had died of blood poisoning due to a miscarriage. The prosecution charged that Hugh Peoples was involved with Annie in an illicit relationship. He was married, and when she became pregnant he went to Dr. Hollywood to have an abortion performed that killed her. In August 1882, the prosecution stated that as nothing had been done in the way of preparation for the trial, it was useless to proceed. The case was dismissed. Despite the verdicts handed down in both cases, the citizens of Detroit were outraged, claiming both abortionists got away with murder. In December 1885, the Bay City Stone Company placed a granite monument inscribed "Anna M. Clemans, born October 23, 1853, died April 7, 1880."  Dr. Cox was accused of malpractice again in 1886 when he performed an abortion on another woman and killed her Dr. Cox was accused of malpractice again in 1886 when he performed an abortion on another woman and killed her In 1886, Dr. William G. Cox was under arrest again for procuring an abortion upon Jennie Phillips which caused her death. Jennie Phillips had come to Detroit six years before from England along with a younger sister. She first worked as a domestic, and then in a factory, but the last two years she worked from a brothel. Letters from her sister Fanny Rintoul, who now lived in Canada were found amongst her things. When she lay dying she said Ferguson was the father of the child, and that he used to live at 318 Humboldt Avenue before he left for Kansas. Due to Cox's prior acquittals, Jennie Phillip's autopsy had 15 doctors in attendance, all who concluded she died from blood poisoning brought about by "malpractice" which was a euphemism for abortion. In March 1887, he was tried for manslaughter, and it ended with a hung jury. It turned out Jennie's birth surname was Armstrong, and she had two sisters, Fanny and Jane. Both of them lived into old age and had several children, living out their lives in Canada.  The death of Hugh S. Peoples was ignominious The death of Hugh S. Peoples was ignominious All those involved in the deaths of Annie Clemens and Martha Whitla did not live happy or long lives. Mrs. Snyder the brothel madame, remarried and became Harriet McGrath, the housewife. In August 1885, when she was 45 years old, she dropped dead in the kitchen of her home. It was attributed to heart disease, even though she had frothed at the mouth, leading some to believe she had taken poison. Dr. James Hollywood died in April 1893, after being thrown from his carriage. He was 70 years old. The stigma of the Clemans trial followed him around until his death. Hugh S. Peoples, born in Ireland, died on August 3, 1894, at the age of 48. He died from a fractured skull while going down the stairs in Lennane's saloon at 9 Cadillac Square. He was very drunk. The truth of his relationship with Martha Whitla did not come out until 1881, when he tried to sue two newspapers for libel. His sister-in-law Agnes Peoples married his brother William. Her maiden name was Whitla and she told the courts of Martha's sad story. Martha's mother had died when she was 2 weeks old, and her father had died before her mother. She had a brother and a sister. Their last name was Pugh. She said that Martha had never been officially adopted by her parents but took that name when she went to school. She lived in the Whitla household until she was 18 years old, and then moved in with her. Martha did the housework for Hugh S. Peoples and his sister, and he gave her a note for $400 for services that she had rendered for him during the years. At that time Hugh was in twenties. They occasionally went out to parties together. During the time Martha lived with Agnes, she wasn't paid, and was just given clothes. Martha had shown various people the note where Hugh Peoples promised to pay her $400. Eventually William Peoples assume payment of the note in order to satisfy $400 he had borrowed from his brother Hugh. Agnes Peoples said she had last seen Martha in September before she disappeared, and that she was living at the Theis household. So the motive of doing away with Martha had nothing to do with a debt, and more like an inconvenient pregnancy. In 1891, Dr. Cox once more found himself charged with criminal malpractice. He was sentenced to one year in the House of Correction and he had to pay a $500 fine. By then he had been arrested six times. He served his time, but this did not seem to deter him since in 1897, he was arraigned on the charge of abortion. By the end of the year, he was found not guilty and set free. In August 1898, Dr. Cox made the newspapers again after performing another abortion for $10. The woman didn't have all the money, and he settled for $5. Like the other trials, he was found not guilty. In 1900, Dr. William Gerow Cox moved to Miami, Florida, but by his death in 1909, he had come back to New York. He was 78 years old.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed