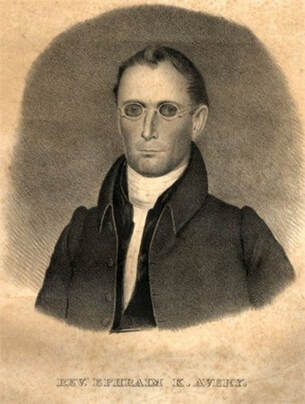

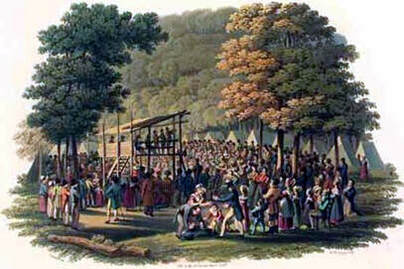

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories Most people are familiar with the notorious murder committed in Fall River, Massachusetts by the axe-wielding Lizzie Borden in 1892. However there was another crime just as heinous that occurred 60 years before.  Rev. Avery Rev. Avery In 1832, Sarah Maria Cornell, 30, died from what was assumed to be suicide by hanging. She was found fastened to a stake-pole used to dry hay. Her reason for ending her life was thought to be the shame of being pregnant and unwed. She was buried, but didn't stay there for long. She was last seen when she left the Fall River Manufactory where she worked around 6 p.m. the day before the discovery of her body. Whispered rumors were that Rev. Ephraim Avery had driven Sarah to her act of self-destruction, or that perhaps she was murdered due to her pregnancy and the scandal it would cause. The body was exhumed, and it had marks of violence. The small cord around her neck was examined and the form of the knot, which had cut in entirely around the throat and neck, could not have happened if she had hung herself. She also had marks upon her cheek in which the murderer placed his foot or knee upon it, as he tightened the cord. There were portions of skin stripped from her leg where she was dragged from the spot when she was strangled, and where it was found suspended. The farm belonged to Capt. Durfee located in Tiverton, Rhode Island a little south of Fall River village. During that evening when she was killed, a teamster passing through the area heard groaning but assumed it was a dying animal and took no further notice.  The murder of Sarah Cornell pitted two religions against each other The murder of Sarah Cornell pitted two religions against each other Sarah came from a good family, however her parent's marriage was unhappy. Her mother, Lucretia Leffingwell's future was assured since she belonged to a genteel family from Woodstock, Connecticut. However she fell in love and eloped with James Cornell, a paper-cutter employed by her father. Against her family's wishes she married him in 1796. She failed to see he was just a fortune hunter. During the next six years, the marriage produced three children, James, Lucretia and Sarah. Urged by her husband, Lucretia asked her father for money, until one day he cut her off. Cornell deserted his wife and their children at her parent's doorstep. It was said he left to the Ohio frontier. The family never heard from him again. The Leffingwell family did not forgive Lucretia for her disobedience. James and Lucretia were brought up by relatives. James would become a merchant and Lucretia married Grindal Rawson, a tailor. It was only Sarah, who was an infant, who stayed with her mother. When she was 11 years old, she went to live with her aunt Joanna. During the 1820s, Sarah worked as a tailor, but found she could make more money by working in the textile factories as a weaver. These mills were proliferating throughout New England. She did not find a husband and soon resorted to petty theft. Her reputation suffered for it. She drifted from town to town engaging in sexual adventures with different men. She tried changing her name in an effort to outrun her reputation, only to once again commit another indiscretion. These were times when a single woman seen walking by herself with a man could damage her standing in society. Before her death she had been expelled from the Methodist church for being a "bad character" and wanted desperately to be reinstated. Sarah's misconduct led her to be an outcast. At some point she realized she could not escape the damage done to her name. She tried to make amends with her mother and sister. She joined the Congregational Church and then the Episcopal Methodist Church, where she attended their tent meetings. In 1828, she arrived in Lowell, Massachusetts, which had a thriving industrial center. She carried with her a certificate of membership in the Methodist Church, which could help her secure employment. For a woman with a damaged reputation, this could mean whether she starved or ate. Sarah found work and had to live in a boarding house owned by the factory, but gossip of her past still hounded her.  Illustration of Sarah Cornell c.1833 Illustration of Sarah Cornell c.1833 Ephraim Kingsbury Avery, was born to Amos and Abigail Avery in 1799. He married Sophia Wells. They had six children, four which lived into adulthood. He had no wish to follow in his father's footsteps as a farmer, so he studied as a doctor but didn't complete the lessons. From there he worked at a general store, followed by a job as a school teacher. Ultimately he moved on to become a minister. Becoming a Methodist minister did not require special training, only that the person accept church discipline and that they could preach. Avery was a handsome man who swayed female converts. It was in 1830 that Sarah and Avery's paths crossed, when she decided to seek employment as a servant. She applied at the home of Reverend Ephraim Avery. Three years before he would face a murder trial, Avery already had a troubled reputation among his flock. He was known for reporting on their bad behavior and pointing out their loose morals. The hierarchy in the Methodist Church allowed him to grant or deny a person a certificate of membership, which could end with banishment or the inability to find work. Later during his trial, Avery denied hiring her, but a witness came forward to say that Avery's wife dismissed the woman after one week because she didn't like the attention her husband gave her. Sarah returned to the mills, but she attempted to get a good reference from Avery, perhaps in hopes of securing another job as a domestic. However this seemed to go against his insistence of discrediting those he considered amoral. No doubt he was attracted and repelled by Sarah. He told her he would give her a certificate if she made a statement describing her bad behavior. She gave him what she wanted, and he gave her the certificate. But since now he had proof of her sins, he initiated a church trial against her. A bout of a sexually transmitted disease urged her from the town, and she drifted to other places, looking for a place to work. In hand she had Avery's certificate. He would give a full history of Sarah's sordid past to any minister inquiring about her. Eventually Sarah went to live with her sister in Woodstock. Her brother-in-law employed her as a seamstress in his shop. Her only troubles were the thought that Rev. Avery held her letters of confession, which he could use against her at any time. She wrote him several times to Bristol, Rhode Island where Avery now lived. In August, 1832, there was a Methodist tent meeting in Thompson, Connecticut. She possibly told him she would be looking for him there, and he tried everything to get her thrown out from the grounds. However according to Sarah he met her later in the forest nearby. She agreed to have sexual intercourse with him in exchange for her letters. During the trial, her pregnancy coincided with a child conceived around this time. Their roles had changed. He gave her the letters back, but now she had his child in her belly. A lawyer suggested she move to Fall River, close to Bristol so she could negotiate support from him. She found work at the Fall River Manufactory. The only thing he had was the prestige of his standing as a Methodist minister. When she begged him not to accuse her once more of loose morals, he responded that he had done nothing, and that she had destroyed herself. On October 20, 1832, Avery disappeared from a religious meeting for about an hour. Sarah confessed he met with her in order to give her a reference to secure employment with Dr. Thomas Wilbur. Dr. Wilbur examined Sarah, and no doubt he questioned her about the paternity of her child. He was very troubled when she told him that Avery had told her to take 30 drops of oil of tansy, which could induce a miscarriage. The dose would also have killed her. Due to Dr. Wilbur's intervention, Sarah's pregnancy proceeded, and for the next two months the two corresponded secretly. After her death there were unsigned letters in a handwriting that could not be definitely proven to belong to Avery. There was a meeting planned for December 20, 1832, in Fall River with an unnamed person. Only the initials B.H. were mentioned, which corresponded with Betsey Hill, Avery's niece. On that day she left work at the mill, ate supper at the boarding house and left a note that read: "If I should be missing enquire of the Rev. Mr. Avery of Bristol he will know where I am. Dec 20th S M Cornell." She was found dead the next day. The hasty verdict of suicide was rescinded once a bandbox where she kept correspondence was found. Her body was exhumed.  A rendition of Sarah Cornell's murder A rendition of Sarah Cornell's murder Once Sarah's death was investigated as a murder, the unsigned letters pointed to a perpetrator close to her. One cautioned her not to address her letters to the writer, as he suspected that one of the missives had been opened before he received it. It directed her to send them to Betsey Hill, Avery's lame niece who lived in his home. During the trial, it was pointed out that this would afford Avery an excuse to take out any letters addressed to Betsey. Another letter laid out a place of assignation to talk over her "situation". Sarah's last note, and the testimony of Dr. Wilbur laid the murder at Avery's feet.  Rev. Avery was portrayed as being in league with the devil when he seduced Sarah Cornell Rev. Avery was portrayed as being in league with the devil when he seduced Sarah Cornell At the second inquest a verdict of "Willful murder against Rev. Ephraim K. Avery" was rendered. This was a serious accusation since he was a Methodist minister with a wife and several children. He was arrested. Witnesses were questioned among them the engineer of the steamboat King Philip who took a letter to Sarah from Avery, which he had instructed to be given directly into her hands. Another Methodist minister, Ira Bidwell who first described Sarah as a "virtuous girl" distanced himself from her. Unclaimed by her family or any Methodist congregation, the Fall River Congregationalist Church buried her as an indigent. It didn't help there was hostility against the Methodists at that time in Fall River. The populations of Massachusetts and Rhode Island were mostly Congregationalists, and were suspicious of the Methodist Episcopal Church that some equated with Freemasonry.  Methodist camp meeting c.1819 Methodist camp meeting c.1819 Avery's trial commenced in May, 1833. The church hired six lawyers to defend Avery. There was a parade of witnesses for either side, 68 for the prosecution and 128 for the defense. Avery's lawyers called into question Cornell's morals, describing her as "utterly abandoned, unprincipled, profligate." The had witnesses testify about her promiscuity, mental instability and expressions of ending her life. She had once contracted gonorrhea, which became known when the doctor that treated her came looking to be paid after she had left town without settling the bill. The prosecution portrayed the Methodist Church as dangerous, and willing to defend their minister and the name of the church at whatever cost, even if it meant covering up a murder. After 16 hours of deliberation the jury found Avery not guilty. He returned to the Methodist Church but public opinion was against him. Effigies of the minister were hanged and burned, and he was almost lynched in Boston. Another letter from Sarah describing her relationship with Avery was found, and a deputy sheriff from Bristol County set off in search of the minister, who had slipped off secretly to New Hampshire. He was brought back to Rhode Island, and the hostile environment of Tiverton. The Methodist Conference once more hired good lawyers to defend Avery. Sarah's body was exhumed a second time, and signs of an attempted abortion and/or sexual abuse were found. It was now May, 1833. The state also placed experienced lawyers as prosecutors including D.J. Pearce who gave up his seat in Congress to prosecute the case. The trial lasted 21 days, and 238 witnesses testified. Among the indictments brought against Avery were that he had been “moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil”. The prosecution hoped to prove there was a relationship between Sarah and Avery, and that he was the father of her child as based on her confessions to the doctor. One of the witnesses was one of four women who had prepared Sarah's body for burial. She testified the woman had been "dreadfully abused." When Dr. Wilbur took the stand and was asked about Sarah's confession, the defense objected the testimony was hearsay and not admissible. Another doctor who testified for the defense claimed that he believed Sarah was insane, but the defense pointed out that the good doctor was Avery's personal physician. Another doctor testified that Sarah's pregnancy was too far advanced for conception to have taken place during the Thompson Methodist meeting. An attorney for the defense declared that suicide “may almost be called the natural death of the prostitute," and that “if you were to seek for some of the vilest monsters in wickedness and depravity, you would find them in the female form." The defense claimed that Avery, a righteous man was being framed by Sarah Cornell. Reverend Avery was found not guilty again. Avery went before the Methodist Conference for a third trial, and unsurprisingly he was found not guilty of any offense. If found not guilty in a court of justice, in the court of public opinion he was very guilty. On a trip to Boston he was surrounded by hundreds of angry citizens. A ditty was made up about Reverend Avery: He killed the mother—then the child  Portraits of Rev. Avery and his wife Sophia Portraits of Rev. Avery and his wife Sophia Soon a play opened in various cities based on the crime. It was titled: The Factory Girl, Or, The Fall River Murder. The anger was not only against Avery but the Methodist religion. In 1834, Avery published Vindication of the Result of the Trial of Reverend Ephraim K. Avery, etc, which the Methodist Church collaborated with him on. Avery was suspended from the Methodist Conference in 1833, and he resigned in 1835. He left to New York and worked as a farmer. In 1851, he left to Pittsfield, Ohio with wife, children and his sister Nabby. Besides farming he acted as a coroner since he had a medical education. Ephraim died in 1869, and Sophia in 1876. The family is buried in the South Cemetery in Pittsfield. Durfee Farm where Sarah was found is the present day site of Kennedy Park in Fall River. Source - Fall River Outrage: Life, Murder, and Justice in Early Industrial New England (1986)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed