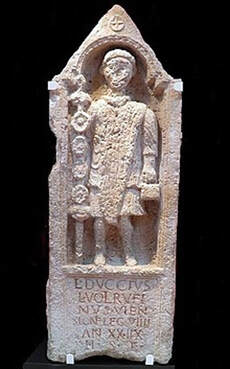

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories In June, 2023, it was announced that a silver military metal with a Medusa motif, was found in what was once the northern edge of the Roman Empire in Britain. Could it have belonged to an ill-fated member of the 9th Legion?  The snake-covered medal dates back approximately 1,800 years. It was unearthed on June 6, 2023, at the archaeological site Vindolanda. This was the site of a Roman auxiliary fort built about 100 A.D., about 20 years before the construction of Hadrian's Wall. The phalera (military decoration) was found under a barrack floor. The motif is Medusa, which is mostly known in the Greek story where Perseus beheads her while she sleeps by using Athena's shield as a mirror. The Medusa also known as Gorga, was one of three Gorgons. They were described as winged human females, with snakes growing from their head instead of hair, and looking into their eyes would turn a person into stone. However by Roman times, Medusa's image was used to repel evil and to stop bad things from happening to the wearer. The snake-haired image has been found on Roman-era tombs, villas and battle armor. Alexander the Great was pictured in a 1st-century mosaic with a Medusa on his breastplate. The phalerae were awarded for "valor in battle" and they would be worn with a strap. Most medals are found in burials.  A stamp of the 9th Legion from a fortress in Caerleon in southern Wales A stamp of the 9th Legion from a fortress in Caerleon in southern Wales Around the time the wearer of this phalerae lost his medal, the Legio IX Hispana (9th Spanish Legion) had already fought in Britain and various provinces throughout the Roman Empire. It was one of the oldest and most feared units in the Roman army. The 9th Legion fought in the siege of Asculum in 90 B.C. In 65 B.C. Pompey raised them to march in campaigns from Gaul to Africa, Sicily to Spain and Germania Inferior to Britannia. Upon becoming governor of Cisalpine Gaul in 58 B.C., Julius Caesar had four legions that were already based there. They were the VII, VIII, IX and X. Caesar disbanded them after his final victory and settled the veterans in Picernum (Abruzzo, Italy). After Caesar's murder there was an attempt to recreate the 7th, 8th and 9th legion, but it wasn't until Octavian took power that he recalled the veterans of the Ninth to fight in the Balkans, where they received the title Macedonica. They battled against Sextus Pompeius in Sicily in 35 B.C. Octavian then used them in other battles including the Battle of Actium against Mark Antony in 31 B.C. In Hispania Tarraconensis (Spain) they battled the Cantabrians (25-19 B.C.). This is when the name Hispana was attached to the legion. In 43 A.D., they most likely participated in the invasion of Britain. In 61 A.D. they suffered a defeat in the rebellion of Boudica. Most of the foot soldiers were killed and only the cavalry escaped. In 71 A.D. they battled the Brigantes, and constructed a fortress at Eboracum (York). Ten years later they were under the command of Agricola for the invasion of Caledonia (Scotland).  The fate of the Roman 9th Legion has puzzled scholars for decades (Source - Radu Oltean) The fate of the Roman 9th Legion has puzzled scholars for decades (Source - Radu Oltean) The last activity for the 9th in Britain was found recorded in a stone tablet discovered in 1864, when they were rebuilding the legionary fortress at York. The legion mysteriously disappeared from Roman records after 120 A.D. without explanation of what happened to them. The fate of the men has been well researched, but without a definitive conclusion of what befell the legion it was theorized they were defeated to the man around 108 A.D. in northern Britain. However there were other mentions made of the IX Hispana at Nijmegen (Netherlands) around 120 A.D. There is even a possibility they were destroyed sometime in 200 A.D. The only certain fact is that the IX Hispana did not exist during the reign of the emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 A.D.). At this time there were 33 legions, and two different lists of legions do not have them recorded.  Memorial to Lucius Duccius Rufinus, standard bearer of the Ninth. Memorial to Lucius Duccius Rufinus, standard bearer of the Ninth. In the 1990s, a silver-plated phalera with "LEG HISP IX" was found at a fortress on the lower Rhine River dating to 104-120 A.D. An altar to Apollo from the same time period found at Aachen, Germany makes reference to Lucius Latinius Macer as chief centurion and prefect of the camp of IX Hispana. He had built the altar in fulfillment of a vow. What is not clear is whether the entire legion, or only a detachment was at the Netherlands. Scholars believe the presence of a senior officer like Macer indicated the whole legion was there. With uncertain information available, the traditional theory was that the Ninth met their fate on the frontier again the Celtic tribes. Possibly a revolt of the Brigantes soon after 108 A.D. was the battle that decimated the legion. One factor that goes against this theory is that two senior officers, who were deputy commanders of the 9th circa 120 A.D. lived on for many years afterwards.  Silchester eagle Silchester eagle In 1866, a Roman bronze casting of an eagle dated to the 1st or 2nd century A.D. was found in Silchester, Hampshire, England during an excavation of a Roman basilica. It was hollowed inside, measured 6 inches in height, but was damaged and the wings were missing. The feet were curved, and it's theorized it was grasping a globe held by a statute of Jupiter. Rosemary Sutcliffe, author of The Eagle of the Ninth (1954), created her story based on the disappearance of the 9th Legion and the discovery of the Silchester Eagle. The movie The Eagle (2011) was based on her novel. The demise of the Legion, which numbered 5,000 of Rome's finest soldiers is argued to have happened either in Northern Britain, or in the east of the Roman Empire. There are several wars that could account for the end of the 9th Legion. In 132 A.D. the Romans fought the Second Jewish Revolt in Judea, and some believe this is when the 9th ceased to exist.  Claudius II (left), Maximinus II (right) (Source - Ohio State Univ) Claudius II (left), Maximinus II (right) (Source - Ohio State Univ) Perhaps it wasn't destruction, but an act of attrition which ended the 9th. Veterans aged out beyond the time they could be recalled. Or maybe the answer is much more mysterious than originally suspected. In 1963, a construction engineer found a small hoard of coins, while excavating the north bank of the Ohio River during construction of the Sherman Minton Bridge for Interstate Highway 64 at the Falls of the Ohio. The coins were grouped as though they had originally been in a leather pouch that had long since disintegrated. As author David Brody explains in his book Romerica (2020): Scores of Roman-era coins, artifacts and fortifications have been found across New England and the Ohio River Valley. They didn’t just swim across the Atlantic on their own, of course. Most of them seem to date back to the 2nd century AD, around the same time that the Roman Ninth Legion—originally stationed in Great Britain—disappeared from history after deploying to Jerusalem to put down the Bar Kokhba uprising. Did members of the Roman Ninth Legion journey to America in the 2nd century? If so, is it possible they brought with them some of the lost Temple treasures?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed