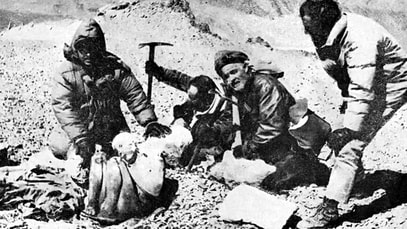

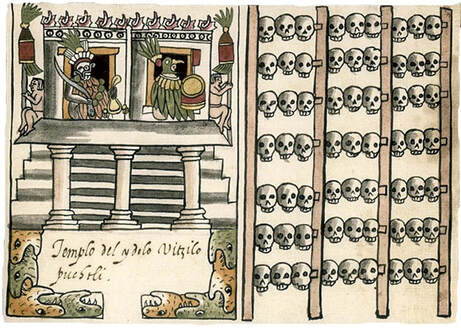

By M.P. Pellicer | Stranger Than Fiction Stories Pachamama Raymi is celebrated on August 1, every year. This festival dates to pre-Hispanic times like the Mayan new year. She is an ancient female deity worshiped by the Mesoamericans and their descendants, even though originally the sun was the main god of the Incas.  Pachamama rituals continue into present times Pachamama rituals continue into present times Pachamama is made from the Quechua word "pacha" which means space, and mama for mother. For the Aymara and the Quechua who have lived in northwestern Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru for hundreds of years the date signifies the beginning of the month when the Earth rests. This is the coldest season of the year in the southern hemisphere. This is when the earth is the hungriest. For this population, their worldview involved duality. Each female thing had to have her male counterpart. For this reason they sacrificed two animals, male and female. Tributes called "challas" in the Quechua language are ritual objects used in the ceremony. The best known is when Mother Earth is "fed". A well is made in the earth, where it is smoked to drive away evil spirits, then around noon on August 1, offerings are left there. These include food, coca leaves, chicha and alcohol among other things that are deposited to feed and drink the Pachamama. These offerings are called huacas in Peru, which are also left in caves or dark places.  El Plomo boy is an Incan mummy discovered in 1954 in Chile. The boy is 500 years old, and was 5 to 8 years old. He wore jewelry and had pouches containing his baby teeth and nail clippings. El Plomo boy is an Incan mummy discovered in 1954 in Chile. The boy is 500 years old, and was 5 to 8 years old. He wore jewelry and had pouches containing his baby teeth and nail clippings. Another tradition is the consumption of male rue cane that's macerated in advance of the festival. It's drunk on an empty stomach, which is suppose to strengthen the drinker and drive away evil spirits for the entire year. However there is a darker side to offerings made to Pachamama. In 2015, the Mars Gaming expedition discovered a complex in Peru used by the Incas during the 15th century to worship gods in times of natural disasters and drought. The place is about 90 miles from Cuzco. They found a necropolis in caves. They unearthed sacrificed children who are called Capacochaes or Capac Cocha. Due to the repetition of the rituals, a series of ceremonial centers were built throughout the Incan land at high altitudes. The sacrifices were done to curry the favor or appease the anger of Pachamama. Only pure children who were physically beautiful and without defects were chosen. They came from good families who by giving up one of their children ascended politically in the Inca empire. Sometimes older children of lower status were sacrificed as servants. María Rostworowski, an expert in Inca culture described the ceremony of Capac Cocha (child sacrifice) on the occasion of the coronation of Pachacutec as supreme sovereign of the Incas, between 1530 and 1540: At the moment that the two hundred children, two by two, male and female, left for the temple, the priests began the prayers to the Inti in order to achieve luck and prosperity for the sovereign. They chose, for the purpose, the most beautiful children, which had no blemish or deformity, which they adorned, for the occasion, with luxurious clothes. The chief of the priests, the villac umu, began the first sacrifice by offering it to the Maker, prayed for a long life for the Inca, for his future victories, and made this prayer by drowning the children, giving them first to eat and drink to those who were old and to the little ones their mothers, saying that they should not arrive hungry or discontented to where the Maker was. The same ceremony was repeated to the idol of the Sun, to the Thunder, to the huaca of Huanacauri and to Pachamama with the invocation of: 'Oh! Mother Earth! to your son the Inca have him, above you, still and peaceful.' The children were drowned and buried along with numerous gold and silver crockery and precious shells.  La Reina del Cerro (Queen of the Mountain) c.1924 La Reina del Cerro (Queen of the Mountain) c.1924 For much of the 20th century many specialists and activists denied the existence of human sacrifices in Inca culture. With the first discovery of mummies in 1905, it was argued that it was a sporadic practice. An expedition was mounted and the mummified body of a 5-year-old child, along with funerary objects were brought down. After the arrival of the Spanish, several Catholic priests described this practice, but until this discovery there was no proof. The consensus among archaeologists was that it was an exaggeration or propaganda of the priests to discredit the Inca cults, when they described how profuse this practice was. Then between 1920 to 1922 Felipe Calpanchay a llama shepherd discovered a tomb on Cerro Chuscha at almost 17,000 feet in altitude. Along with Juan Fernandez Salas a Chilean miner, they dynamited the tomb and brought out the mummified body along with the grave goods inside. The inhabitants of Tolombon call it "Queen of the Mountain". While it was there they lit candles and gave it offerings.  The Queen of the Mountain mummy c.2012 The Queen of the Mountain mummy c.2012 In 1922, Pedro Mendoza a collector and dealer bought the mummy and took it to Cafayate. He exhibited it in one of the oldest houses in the town known as La Casa de Mendoza, where he charged visitors to see it. Two years later he sold it to Perfecto Bustamante, a herbalist from Buenos Aires who displayed it at his shop. In 1924, Professor Amadeo Rodolfo Sirolli beccame aware of the mummy's existence. He took photographs, an inventory of the grave goods that accompanied her, and a detailed description of what she wore. However Sirolli never disclosed this information until 1954. By 1935, Bustamante had died and his widow gave the mummy to Absjorn Pedersen an amateur archaeologist in exchange for a gas installation. He kept it in an attic for 50 years, forgotten and untended. Then in 1977, Sirolli published a paper titled La Momia de los Quilmes (The Mummy of the Quilmes), where he provides all the information he gathered when he inspected the relic along with the photographs taken in 1924. After this publication, the "lost mummy" became the object of a search. In 1979, the only photograph of the mummy was shown on a TV program with hopes it whereabouts could be determined. An antique dealer in San Telmo bought it for $48 in 1985. The dealer offered archaeological objects which included the mummy, and it came into the hands of Carlos Colombano.  Schobinger at the top of Cerro el Toro c.1960s Schobinger at the top of Cerro el Toro c.1960s In 1991, Marcelo Scanu, an explorer saw it exhibited in front of a bank in Buenos Aires on Florida Street. In 2001, the Center for Studies for Applied Policies (CEPPA) acquired the mummy with its grave goods, and initiated the first scientific studies of the young girl sacrificed hundreds of years before. DNA examination of the girl estimated she was about 8.5 years old. She had no intentional cranial deformations, and a year before she died she was eating a normal meal, until six months before her death where she was mostly consuming corn. Her cause of death was a stab through the back, which caused a traumatic hemorrhage, which explained the expression of pain on her face. Examination of her finely braided hair found she had eaten coca leaves as is normally found in ritual victims. It was then that the 15th century stories told by the Europeans seemed to be accurate. In 1964, members of the Club Andino Mercedario discovered a ceremonial mound on the summit of Cerro El Toro that is over 20,000 feet at its highest point. It is located on the Argentine-Chilean border. A whitish object they saw protruding turned out to be the upper part of a human skull. They found the mummy of a young man with his teeth, skin and musculature in perfect condition. Its eyes with a slight Mongolian fold and protruding cheekbones are typical for the Inca people. He was wearing a shirt and loincloth, along with a blanket, double -soled flipflops, a hat and small utensils. He was estimated to have been 18 to 20 years old when he died. Cupped in his hands he had a small mouse that had been decapitated.  Children of Llullaillaco mummy c.1999 Children of Llullaillaco mummy c.1999 In 1974, close to the top of Quehuar volcano a discovery was made of a child mummy. Due to the hard and frozen ground it could not be brought down. It wasn't recovered until 1999. That same years three frozen children with a rich trousseau in perfect condition were found. They became known as the "children of Llullaillaco". They had been killed about 500 years before and due to the richness of their grave goods they were thought to be Inca nobility. DNA found there was no relationship between them. The discoveries of the Mars Gaming expedition confirmed the importance of human sacrifices in the ancient cult of Pachamama. Starting in 2011, archaeologists discovered what turned out to be the largest single mass child sacrifice event in human history on a cliff above the Pacific Ocean, once inhabited by the Chimu. The sacrifice was carried out about 550 years ago, and the remains of 140 children and 200 young llamas were unearthed.  The site of the massive child sacrifices sits just a thousand feet from the Pacific Ocean. It is not far from Chan Chan, which was once the ancient capital of the Chimú Empire. (Source - John Verano) The site of the massive child sacrifices sits just a thousand feet from the Pacific Ocean. It is not far from Chan Chan, which was once the ancient capital of the Chimú Empire. (Source - John Verano) John Verano with Tulane University who was part of the research team said they had found "evidence of the greatest mass sacrifice of children in America and probably in world history, personally, I did not expect it, and I think no one else could have imagined it" The excavations ended in 2016. The temple dated back 3,500 years. Radiocarbon tests date the grave goods back to between 1400 to 1450. "The skeletal remains of the children and animals show evidence of cuts to the sternum, as well as dislocations of the ribs, suggesting that the victims' chests were opened and separated, perhaps to facilitate the removal of the heart." It is theorized the children had been sacrificed to appease the El Niño phenomenon and showed signs of being killed during wet weather. As Alfonso Caso wrote in the book El Pueblo del Sol: "Man has been created by the sacrifice of the gods and must reciprocate by offering them his own blood."  A codex written after the conquest by a Spanish priest depicts Tenochtitlan's enormous skull rack, or tzompantli. C.1587 AZTEC MANUSCRIPT, THE CODEX A codex written after the conquest by a Spanish priest depicts Tenochtitlan's enormous skull rack, or tzompantli. C.1587 AZTEC MANUSCRIPT, THE CODEX Further north into central America and Mexico, chroniclers who accompanied the Spanish described where in 1487 more than 80,000 victims were sacrificed to inaugurate an extension of the Templo Mayor. This was not only the Franciscan and Dominican friars who described this event, but other accounts written in the Nahuatl language corroborate it. Archaeologists and anthropologists through examination of human remains, have found that human sacrifice was widespread throughout Mesoamerica from preclassic times to the arrival of the Spanish. The discovery of the Great Wall of Skulls or Tzompantli excavated in Guatemala Street in the center of Mexico City in 2018, found walls of skulls taken from sacrificial victims. In Mexica culture opposed to the Incan, the sacrificed children have been found to have suffered from acute health problems based on an examination of their teeth and in their nutritional status. For this culture sacrificial victims were either war captives, or those from within their own community. They were chosen according to the deity they would be sacrificed to. They believed the blood of the victim not only fed the gods but regenerated them as well. The most common method consisted of removing the heart of the victim, this was done through different techniques. Sometimes before the extraction of the heart the victim was arrowed, burned or locked in caves to obey the symbolic motif of each deity. Sacrifices to the Mexica goddess Chicomecoatl who presided over vegetation, required a young woman who represented the goddess to be decapitated. The decapitated head was compared to the severed ear of corn. In war, it was not only conquest that was sought, but a source for sacrificial captives. On the battlefield efforts were made not to kill an opponent, but to capture them alive. "Some texts in Nahuatl of the Nahua collaborators of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún describe that some had to be dragged to climb to where they would be sacrificed, others fainted and some more cried with sadness. However, in celebrations where they had to represent an important god such as Tezcatlipoca, some warriors who were offered freedom, rejected it because of the honor that the celebration implied." Sources - Clarin , Infobae , The Guardian

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Stranger Than Fiction StoriesM.P. PellicerAuthor, Narrator and Producer Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Stories of the Supernatural

- Stories of the Supernatural

- Miami Ghost Chronicles

- M.P. Pellicer | Author

- Stranger Than Fiction Stories

- Eerie News

- Supernatural Storytime

-

Astrology Today

- Tarot

- Horoscope

- Zodiac

-

Haunted Places

- Animal Hauntings

- Belleview Biltmore Hotel

- Bobby Mackey's Honky Tonk

- Brookdale Lodge

- Chacachacare Island

- Coral Castle

- Drayton Hall Plantation

- Jonathan Dickinson State Park

- Kreischer Mansion

- Miami Biltmore Hotel

- Miami Forgotten Properties

- Myrtles Plantation

- Pinewood Cemetery

- Rolling Hills Asylum

- St. Ann's Retreat

- Stranahan Cromartie House

- The Devil Tree

- Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum

- West Virginia Penitentiary

- Paranormal Podcasts

"When misguided public opinion honors what is despicable and despises what is honorable, punishes virtue and rewards vice, encourages what is harmful and discourages what is useful, applauds falsehood and smothers truth under indifference or insult, a nation turns its back on progress and can be restored only by the terrible lessons of catastrophe."

- Frederic Bastiat

- Frederic Bastiat

Copyright © 2009-2024 Eleventh Hour LLC. All Rights Reserved ®

DISCLAIMER

DISCLAIMER

RSS Feed

RSS Feed